Appreciate our quality journalism? Please subscribe here

DONATE

One of Australia’s most senior tax officials worked for over a decade directly with two of the tax partners named in consultancy giant PwC’s tax leaks scandal – including Peter Collins, the disgraced accountant at the heart of the affair.

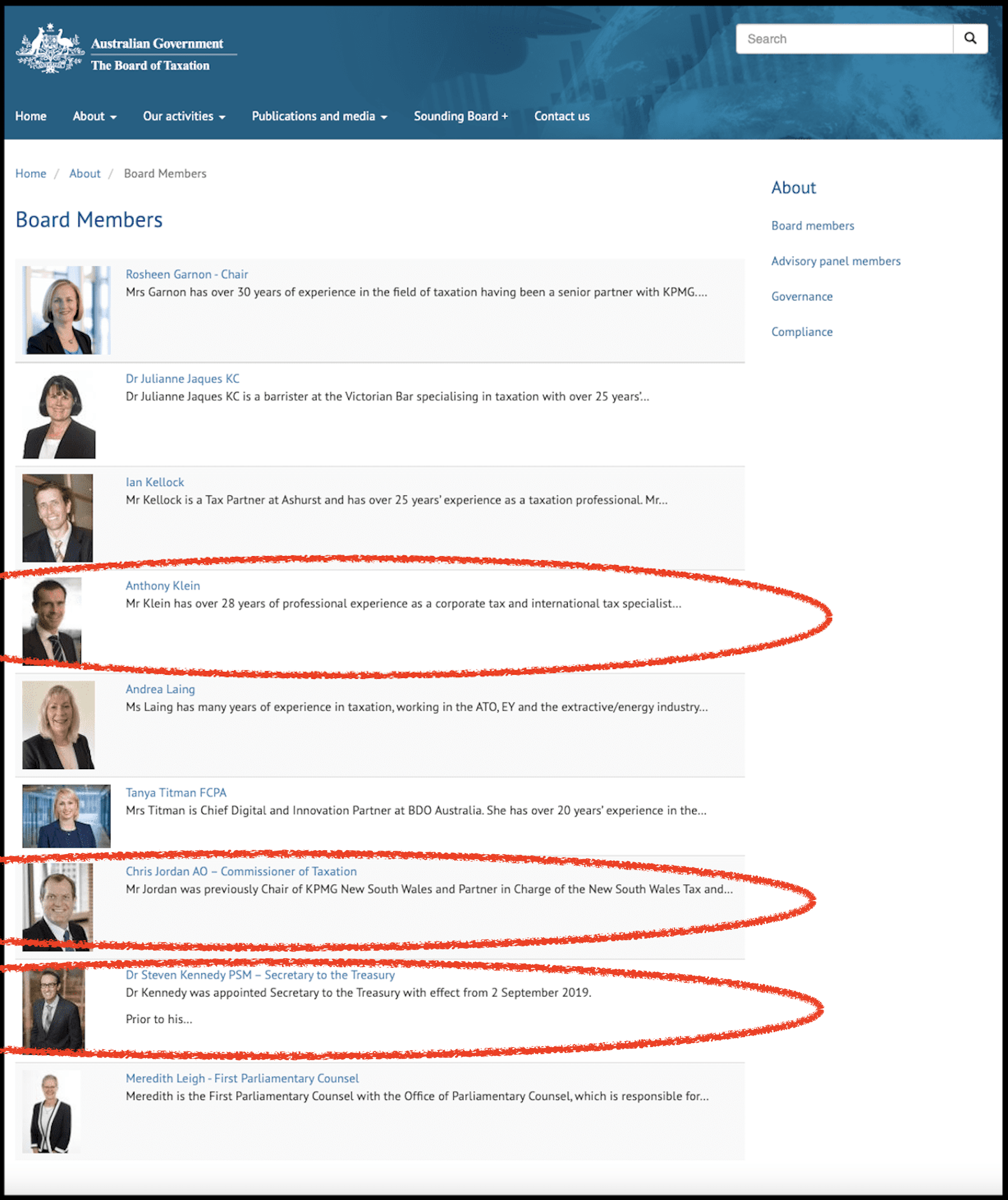

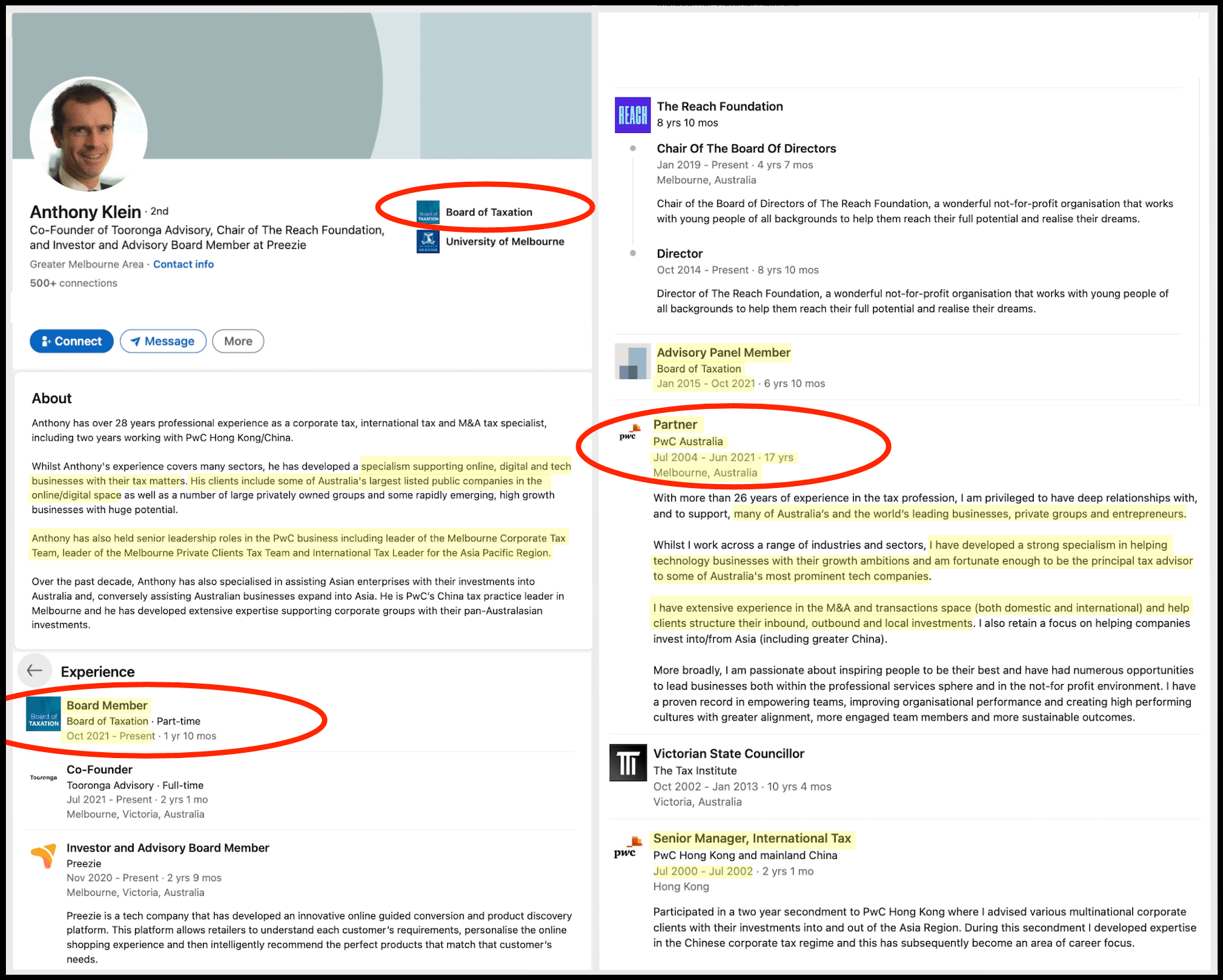

Investigations reveal Australian Board of Taxation director Anthony Klein, a PwC tax partner for 17 years until July 2021, worked directly with both Collins and fellow PwC tax partner Paul McNab, including in direct collaboration at least as recently as October 2018.

That included spruiking for business following an Australian Government “policy paper” about moves to crack down on tax avoidance by multinational tech giants.

Collins and McNab were among the four former tax partners PwC named early last month as tied to the scandal, which is ravaging its Australian operations and sending tremors across its operations worldwide.

As a Board of Taxation director Klein is responsible for “improving the design” of the nation’s tax laws — and sits alongside fellow directors Stephen Kennedy, the Secretary to the Treasury, and Chris Jordan, boss of the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

Klein was appointed to a three-year term as Board of Taxation director, a part-time role with a taxpayer salary of $61,230 a year plus expenses, in October 2021.

Before that he had spent almost seven years as a member of the board’s “Advisory Panel”, starting in January 2015.

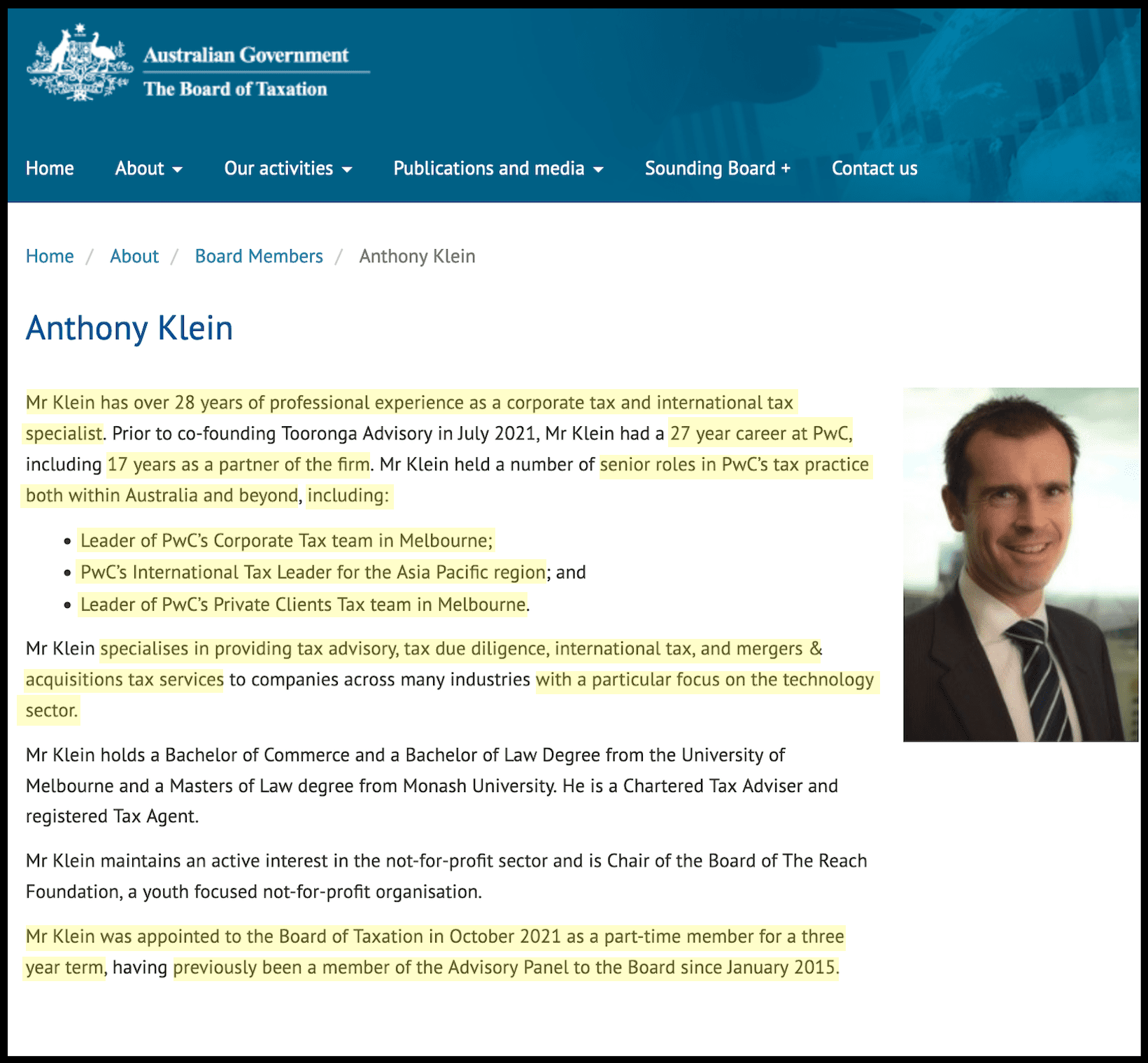

“Mr Klein was appointed to the Board of Taxation in October 2021 as a part-time member for a three-year term, having previously been a member of the Advisory Panel to the Board since January 2015,” the Federal Government’s Taxation Board states.

Please DONATE HERE to help keep us afloat

Directors of the Board of Taxation. Source: Board of Taxation

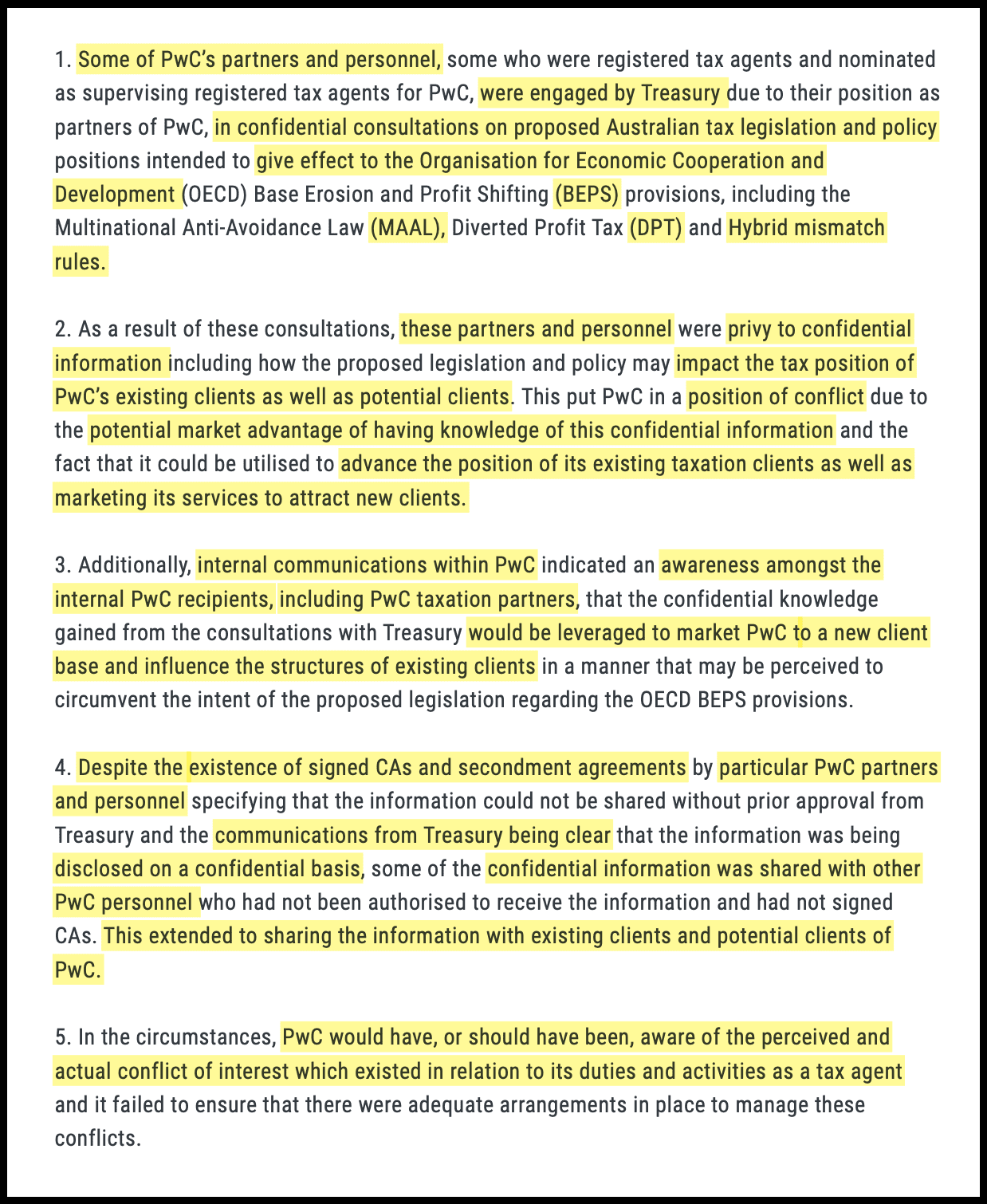

From 2013, PwC took confidential Australian Government data, gleaned while providing “advice” drafting multinational tax avoidance laws — and shared it widely within the firm, both in Australia and globally, as well as with clients and prospective clients.

Under a scheme PwC internally called “Project North America” it aggressively marketed – and sold for millions of dollars – confidential information to US-tech giants with operations in Australia, offering “work arounds” of laws months before they were announced.

Those revelations became public in January when Australian tax authority the Taxation Practitioners Board, which oversees Australia’s 80,000-odd tax agents, revealed it had conducted multi-year investigations into both Collins and PwC over the affair.

PwC initially claimed only Collins, who received a two-year ban, had been involved.

Anthony Klein, Board of Taxation board member since October 2021. Source: LinkedIn

Collins was engaged to give “advice” on creating the new tax laws by the Board of Taxation as well as Australia’s Department of Treasury, where he signed confidentiality agreements in 2013, 2015 and February 2018.

PwC had for months claimed only Collins was involved, despite the Tax Practitioners Board’s investigation into PwC, which it ran alongside the Collins investigation, in January citing multiple unnamed other “PwC partners and personnel”.

That changed after May 2 when, months after it was requested, the Tax Practitioners Board handed over to a Senate inquiry a 144-page dossier of internal PwC emails from 2013 to 2018.

The heavily redacted emails (Collins is the only name not removed) reveal many dozens — if not hundreds — of PwC partners and staffers in Australia and worldwide received emails discussing plans to use confidential government tax policy information to win new clients.

On June 5, and only following extreme pressure, PwC Australia interim CEO Kristin Stubbins named four former PwC tax partners as tied to the scandal: Collins (who had been named in January); Paul McNab; Neil Fuller; and Michael Bersten.

Please DONATE HERE to help keep us afloat

Peter Collins (left), Paul McNab and Anthony Klein. Source: Supplied

Collins quietly departed from PwC in October last year (the multi-year Tax Practitioners Board investigation was completed November 16); McNab resigned from law firm DLA Piper, where he had been a tax partner since he left PwC after 22 years in May 2020, the night before PwC named him on May 2; and Fuller, according to his since-deleted LinkedIn resume, “retired” from PwC in 2019.

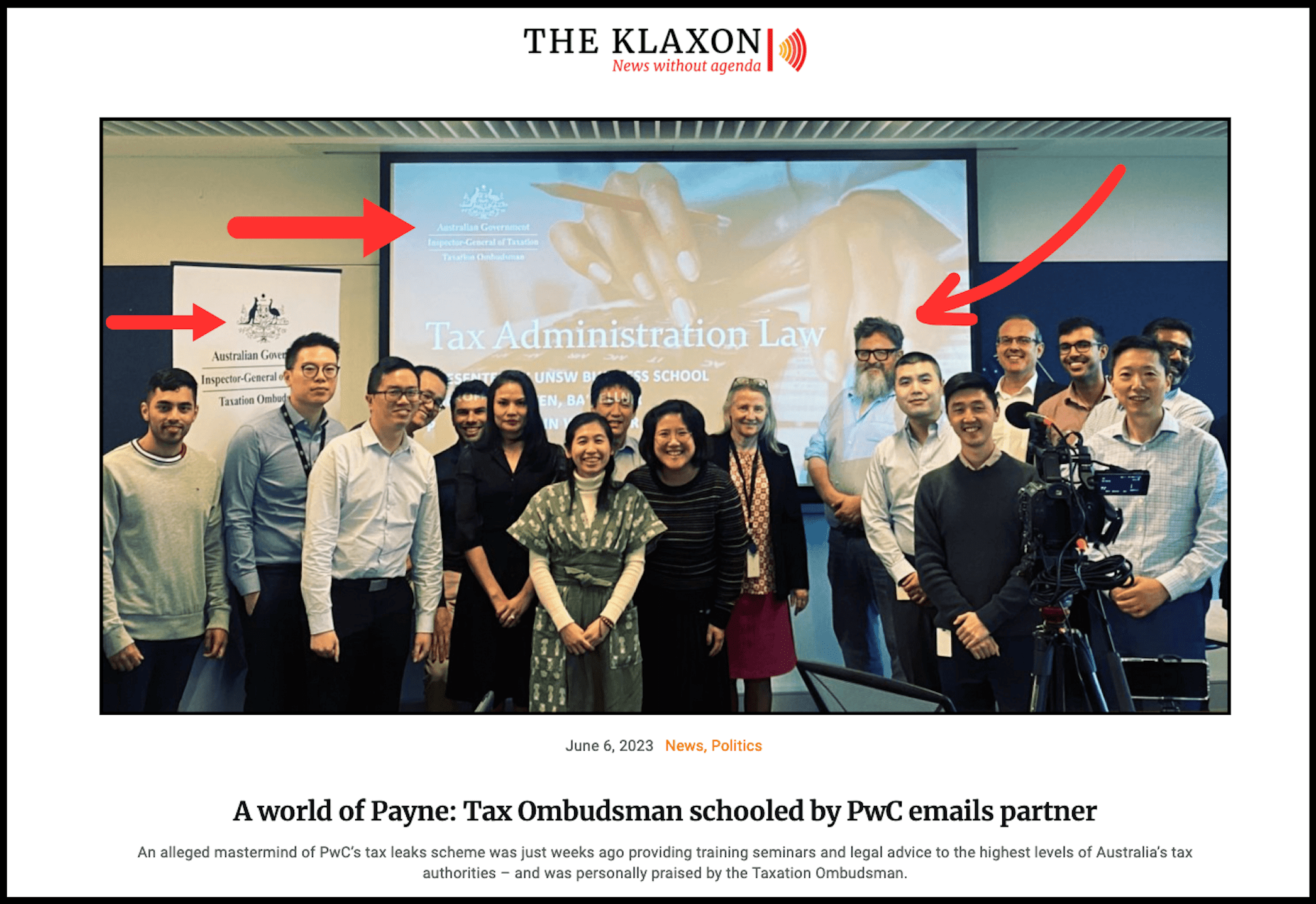

Bersten, who was at PwC Australia from 2004 to July 2018 and “founder” of its “tax controversy” arm, was last month ousted from roles teaching “Tax Administration Law” to hundreds of government tax officials at the ATO and fellow Federal agency, the office of the Inspector-General of Taxation and Taxation Ombudsman (IGTO), after The Klaxon revealed the arrangement on June 6.

Collins, who started at PwC (then Coopers & Lybrand) in 1990, spent his career based in the firm’s Melbourne office, where PwC documents show he was tax partner from at least 2009.

The Klaxon reveals Bersten was running training courses for the ATO and the Taxation Ombudsman. Source: The Klaxon

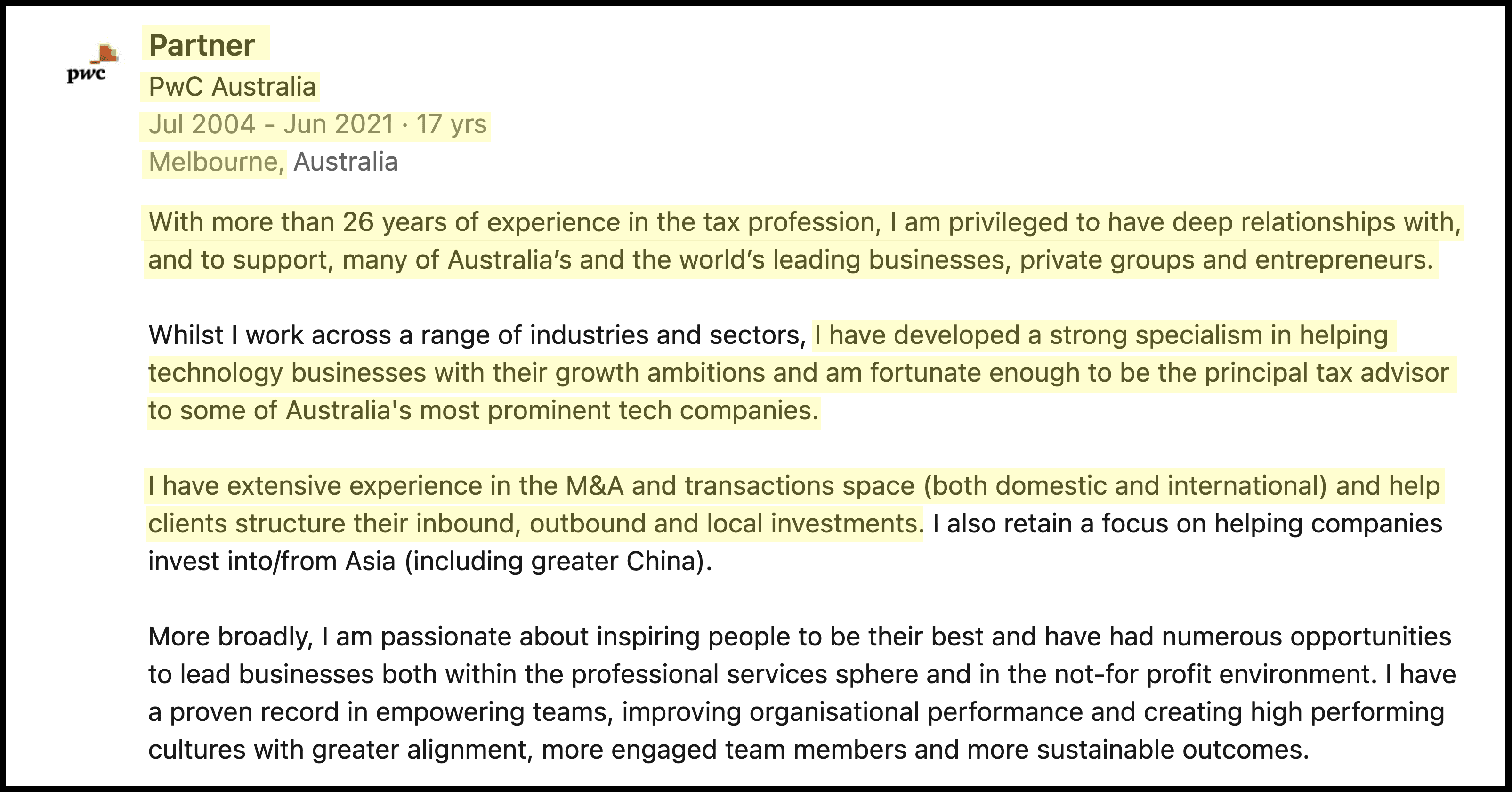

Klein was at PwC, including as “Leader of PwC’s Corporate Tax Team in Melbourne”, from 2004 to June 2021, when he set up Melbourne “tax advisory” consultancy Tooronga Advisory.

Klein’s bio at the Federal Government’s Board of Taxation states he has “over 28 years” as a “corporate tax and international tax specialist” with a “particular focus on the technology sector”.

More on the PwC tax scandal:

June 23: PwC refuses to disclose “terms of reference” to its secret inquiry

June 19: PwC tax boss turned ATO teacher ousted after Klaxon expose

June 9: “Network of tentacles”: Tax board forced to come clean on PwC ties

June 7: “Vanished” Tax Board boss was exec at pre-PwC

June 6: A world of Payne: Tax Ombudsman schooled by PwC emails partner

May 30: AFP refused to take action on PwC: ATO boss

May 30: PwC scores new $164,000 Fed Gov’t contract

May 24: You don’t Sayers? PwC Mini-Me in $6m Gov’t bonanza

It says Klein “held a number of senior roles in PwC’s tax practice both within Australia and beyond”, including “Leader of PwC’s Corporate Tax Team in Melbourne”; “Leader of PwC’s Private Client Team in Melbourne”; and “PwC’s International Tax Leader for the Asia Pacific region”.

“Mr Klein specialises in providing tax advisory, tax due diligence, international tax, and mergers and acquisitions tax services to companies across many industries with a particular focus on the technology sector,” it says.

Please DONATE HERE to help keep us afloat

Board of Taxation director Anthony Klein. Source: Board of Taxation

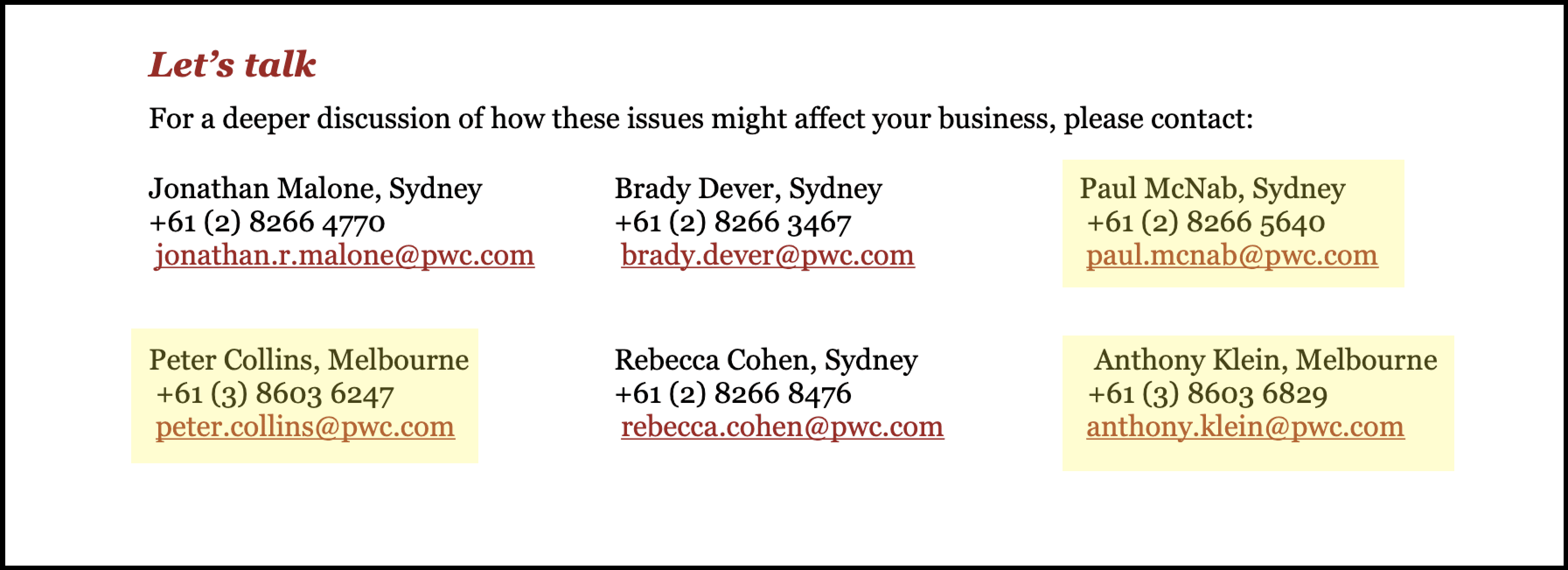

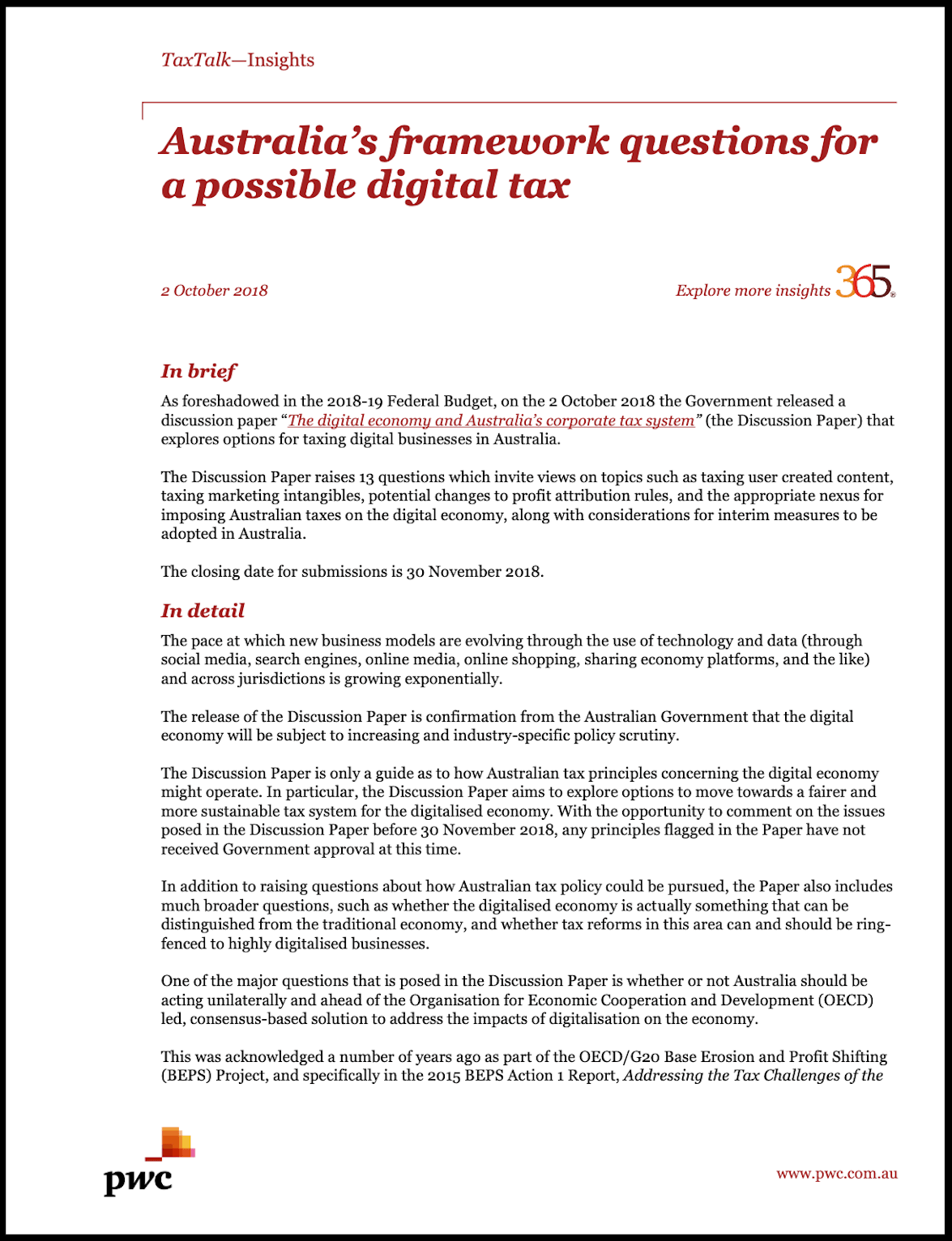

In October 2018 PwC sent a letter to existing and prospective big business clients titled “Australia’s framework question for a possible digital tax”, in response to Australian Government “discussion paper” released that same day.

In it, PwC spruiks for new business and protests the introduction of long-planned new laws aimed at curbing tax avoidance by multinational tech giants.

In the letter Klein, Collins and McNab, along with three other PwC Australia tax partners, warn Australia “should be careful” before “deciding that it has the right to tax the proceeds of services and technology that it neither performs nor creates”.

“It will be important that any proposed changes consider any risk of retaliation by other territories whose companies may be unilaterally impacted if the changes are seen as unfair and inequitable,” the letter states.

Concluding with the words “Let’s talk”, it says for a “deeper discussion” of “how these issues might affect your business”, to contact Klein, Collins, McNab, or three other PwC executives.

The October 2018 letter from the PwC tax partners. Source: PwC

Klein has repeatedly refused to respond for almost three weeks, with The Klaxon approaching him with a series of written questions on June 23, both via the Board of Taxation and his firm Tooronga Advisory.

The Board of Taxation and Stephen Kennedy’s Department of Treasury, which oversees it, also refused to respond to questions sent to them on June 23, including whether Klein’s name appeared in the 144-page cache of internal PwC emails.

“Klein, the Boart of Taxation and Treasury have all refused to respond since June 23”

Refusing to answer: Questions put to Klein and the Board of Taxation’s Rosheen Garnon and Julianne Jaques.

Department of Treasury spokesman Chris O’Brien said Treasury had “referred the PwC matter to the Australian Federal Police” to “consider commencement of a criminal investigation” on May 24.

He said: “The Board of Taxation is not able to comment further on that referral or related questions. It is a matter for the Australian Police”.

When The Klaxon responded that same day, asking to be directed to the “relevant law/guidelines (or similar)” that prevented the Board of Taxation from commenting.

We received no response.

Australia’s four tax agencies. Source: Australian Government; Graphic: The Klaxon

The PwC scandal has drawn the spotlight on vast dependency by the Australian Government on “consultancies”, which exploded under the former Coalition Government, in power from 2013 to May last year.

The Labor Federal Government in May released a bombshell audit finding private businesses were paid a massive $20.8 billion in 2021-22 to deliver public services.

This “shadow public service”, equivalent to 54,000 full-time workers, compared to 144,000 in the Australian Public Sector workforce.

The Centre for Public Integrity, an anti-corruption think tank founded by former top judges, that same month found government contracts to the “Big Four” consultancies — KPMG, PwC, Ernst & Young and Deloitte — had exploded over 400 per cent in the past decade

At the same time political “donations” had surged, with the Big Four “donating” “$4,289,253 to the ALP and Coalition,” it found.

Senator Pocock said the PwC Australia matter represented “a crisis and a scandal”, given major consulting firms between them are given billions of taxpayer funds annually.

On June 24, along with Klein and Treasury, The Klaxon put questions directly to Board of Taxation chair Rosheen Garnon and director Julianne Jaques, who was acting chair from July 2019 to January 2020. Both refused to respond.

Government refusing to respond to questions regarding Anthony Klein.

The Board of Taxation says Garnon, who is paid $122,460 a year plus expenses as chair, “has over 30 years experience” in tax having “been a senior partner of KPMG”, including the “National Managing Partner for KPMG Australia’s Taxation Division” from 2009 to 2015.

Jaques, who like Klein is paid $61,230 a year plus expenses as director, has “over 25 years’ experience as a taxation professional”, previously working as a “solicitor with Freehills (now Herbert Smith Freehills) and an accountant with Coopers & Lybrand (now PriceWaterhouseCoopers)”, the Board of Taxation says.

In mid-2013, in response to a request from the G20 group of nations concerned over the growing billions of lost revenue to tax avoiding multinational tech firms, the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) published a “15 point action plan”.

The “spread of the digital economy”, multinational tax evasion by tech giants had become a “critical issue for all parties” including for governments, individuals and taxpayers, citing the need for “a swift implementation of the measures”, the said.

The umbrella term for multinational tax avoidance is Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, or BEPS, and the OECD called for new laws to be introduced to crack down on a range of tax avoidance schemes, including around “hybrid mismatch arrangements”, “controlled foreign company rules” and “multinational anti-avoidance laws”, or MAAL.

Please DONATE HERE to help keep us afloat

TPB’s findings on PwC, 16 November, 2022. Source: TPB

As part of its response to the OECD plan, the Australian Government on January 1, 2016, announced new MAAL laws.

Last month the ATO told the Senate committee it had serious concerns when, almost immediately, multiple multinationals had already “restructured” to avoid the new laws.

PwC launched Operation North America in 2015, aggressively spruiking to US tech giants confidential information it had gleaned while inside government regarding the incoming MAAL laws, with the internal emails showing it earned $2.5m from just “stage one” of the scam.

Part of TPB findings on Peter Collins, November 16, 2022. Source: TPB

Although much of the focus in the PwC scandal to date has been on MAAL laws the cache of internal PwC emails show scores of partners and staffers, between 2013 and 2018, received emails discussing confidential Australian Government plans for laws around a range of schemes – and how to “work around” those proposed new laws.

the Tax Practitioners Board in January found Collins and other unnamed PwC “partners and personnel” had at Treasury been given access to a range of “confidential information and documentation” regarding “MAAL, the Diverted Profits Tax (DPT) and Hybrid mismatch rules”.

It also found Collins “received confidential information and documentation during the course of his participation in consultations that were facilitated by the Board of Taxation” regarding potential legislation “intended to give effect to the OECD BEPS and anti-hybrids provisions”.

Klein’s LinkedIn bio entry for PwC states he has “more than 26 years of experience in the tax profession” and is “privileged to have deep relationships with…many of Australia’s and the world’s leading businesses, private groups and entrepreneurs”.

“I have extensive experience in the M&A and transactions space (both domestic and international) and help clients structure their inbound, outbound and local investments,” he writes.

“Whilst I work across a range of industries and sectors, I have developed a strong specialism in helping technology businesses with their growth ambitions and am fortunate enough to be the principal tax advisor to some of Australia’s prominent tech companies”.

BEFORE YOU GO! Help us stay afloat and telling these stories. Please SUBSCRIBE HERE or support us by making a DONATION. Thank you!

Anthony Klan

Editor, The Klaxon

Help us get the truth out from as little as $10/month.

Unleash the excitement of playing your favorite casino games from the comfort of your own home or on the go. With real money online casinos in South Africa, the possibilities are endless. Whether you’re into classic slots, progressive jackpots, or live dealer games, you’ll find it all at your fingertips. Join the millions of players enjoying the thrill of real money gambling and see if today is your lucky day!

The need for fearless, independent media has never been greater. Journalism is on its knees – and the media landscape is riddled with vested interests. Please consider subscribing for as little as $10 a month to help us keep holding the powerful to account.