Appreciate our quality journalism? Please subscribe here

DONATE

The jailing of former Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan two weeks ago and an economic crisis exacerbated by crippling debt — much of it from China — is likely to see the South Asian nation become more dependent on Beijing than ever.

Ten years under Beijing’s “Belt and Road Initiative” has seen Pakistan saddled with tens of billions of dollars in extra debt, yet the promised economic returns — that were to be used to make repayments — have failed to materialise.

Last month Pakistan both marked ten years under the massive BRI infrastructure program — and received a last-minute bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), saving the nation from economic collapse.

The IMF’s US$1.2bn, part of the long-delayed ninth review of the “Extended Fund Facility”, is enough to help Pakistan meet its immediate debts, but the nation remains on economic life support.

China and Chinese banks now hold about 30 per cent of Pakistan’s external debt, and many of those loans are for shorter periods and at substantially higher interest rates than loans from elsewhere, such as the IMF and the “Paris Club” group of nations.

Those debts have soared alongside the ambitions and size of the Belt and Road Project: what was announced in 2013 as a five-year tie-up costing US$10bn to US$20bn, is now forecast to run to 2030 at a cost of at least US$62bn.

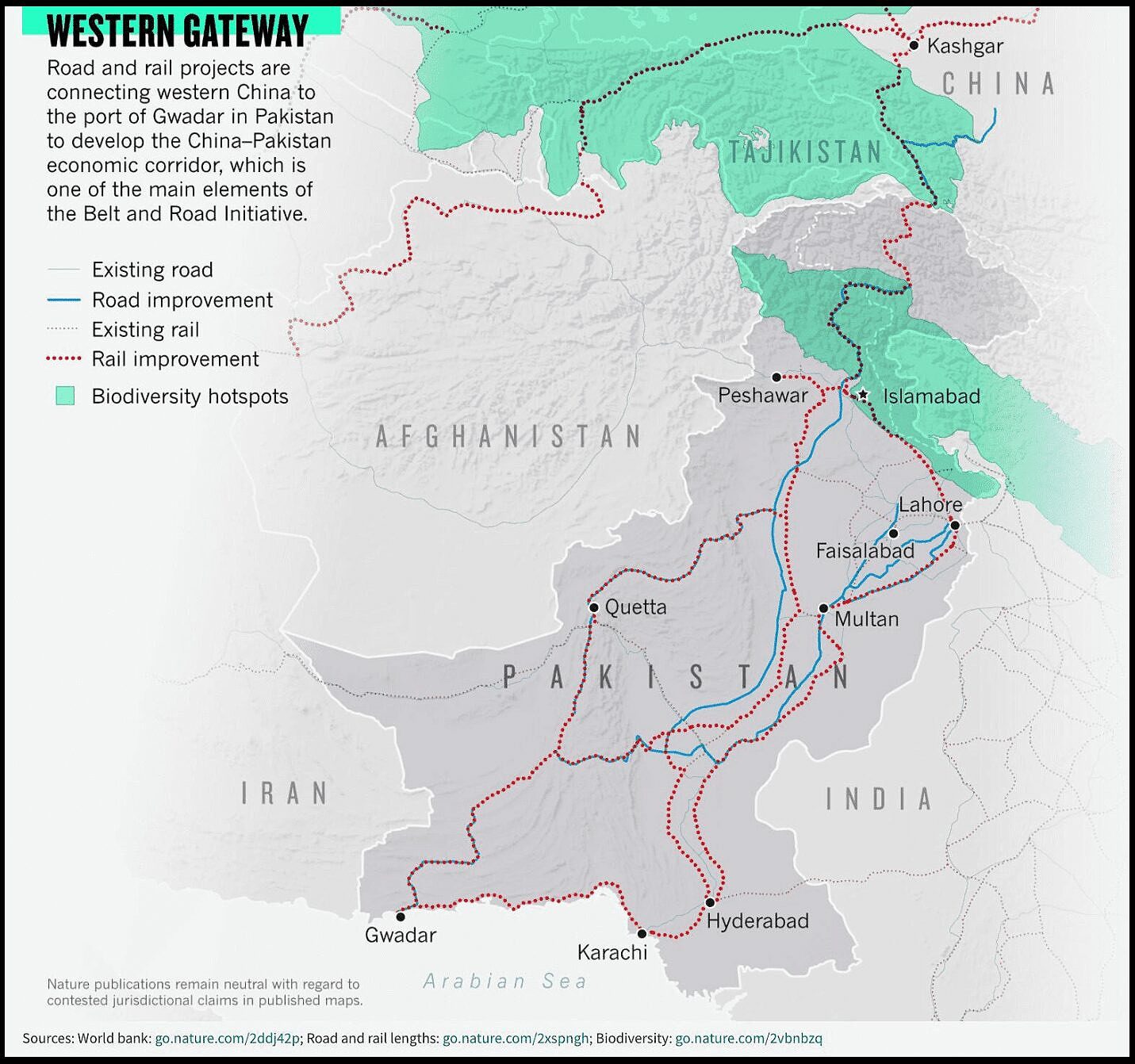

The BRI in Pakistan, also called the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), was initially an infrastructure project connecting China to the Gwadar Port in Pakistan’s south, but almost two-third of projects now relate to electricity generation.

Pakistan is estimated to owe China and Chinese banks about US$30bn, although much of the debt is opaque, suggesting the true figure could be even higher.

Worsening the situation, given most of the debt is in foreign currency, is Pakistan’s runaway inflation, which is running at an annualised rate of almost 30 per cent.

The “China-Pakistan Economic Corridor”, flagship project of the controversial Belt & Road infrastructure scheme. Source: Nature

A failure by Islamabad to initiate long-term economic reforms, along with unease that more loans will simply go to repaying China, has made many lenders increasingly reluctant to assist.

That further increases Pakistan’s economic dependency on China, including through loan refinancing, new loans, or as part of a potential, Beijing-led major economic restructure.

In turn, experts say, that economic dependency makes it more likely China will push for broader concessions, particularly in areas of security, increasing its sway over Islamabad.

Political turmoil roiling the country is also playing into China’s hands.

The jailing last month of cricket super-star turned populist politician Imran Khan, over claims he illegally sold state gifts, sees the Pakistan military firmly back in the driver’s seat.

Imran Khan in New York in September 2019. Source: Supplied

Pakistan’s military, not government, has been a key driver of the Belt and Road tie-up, which has surged ahead despite concerns raised from government, including from Khan.

On coming to power in 2018, Khan “sought a reset” of BRI and his commerce minister told media the former government had done a “bad job negotiating” and “gave a lot away” to China.

Just over a week later, without Khan, Pakistan’s chief-of-staff went to Beijing on “special invitation” of China President Xi Jinping and announced his full support for the program and China.

In a detailed 2020 report, US non-profit research group the Brookings Institution said the “opaque” CPEC mega-project was being driven by Pakistan’s military, with key costing and other details “not revealed to the Pakistani Parliament”.

Pakistan’s general election is due to be held within months, but Kahn’s jailing last month, accompanied with a five-year ban from politics, means he is unable to run.

Khan was helped to power with covert backing from the military, but he fell out with “the establishment” — as the military is known in Pakistan — and was ousted in April last year in a parliamentary vote of no confidence.

Since then Kahn, who remains popular with the public, and has spent much of the year leading in the polls, has run a campaign against the military, which he blames for his ousting.

Pakistan’s military has been in control of the nation for almost half of the time since its British Independence, under four different coups, and it remains behind the levers of power.

Khan’s campaign reached a flashpoint in May, when his arrest and brief detention sparked widespread protests — including attacks on military bases and the homes of military officers — in what was seen by some as the possible seeds of a broader revolution.

The Klaxon reports on the protests. Source: The Klaxon

Since then, the Pakistan military has run a wide-scale crackdown, with Kahn’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party stating thousands of its supporters have been detained.

Multiple Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf senior party figures have resigned, in moves experts say are likely tied to pressure or threat from Pakistan’s military and intelligence agencies.

The existing Coalition government, which has the support of the military, is tipped as the likely winner of the election.

While there have been benefits under the BRI program, notably improved electricity supply with power stations a key component, the promises of long-term economic gains have failed to occur.

Those failings, in part due to Pakistan’s unwillingness or inability to undertake the structural reforms necessary to underpin its long-term stability, vastly magnify the impact of the billions of extra debt.

Khan’s arrest in May. Source: Al Jazeera

They also give considerable weight to long-held serious concerns by the US and many western countries of China using BRI in “debt-trap diplomacy”, by over burdening developing nations with debts they won’t be able to repay, and then taking control of key assets and power structures.

In Pakistan many have been disappointed by Beijing’s insistence on importing materials and labour, leaving Pakistani suppliers and workers out of the mix.

Increasing frustration against China, which many see as exacerbating the nation’s woes, has seen attacks on Chinese nationals.

“There have been targeted attacks on Chinese workers involved in development projects in Balochistan,” says one source.

Uzair Younus, a director of the Pakistan Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Centre, said as Pakistan’s “economic and security crisis worsens” it is increasingly likely China will “retable some key security and geopolitical demands in discussions with Pakistani officials”.

More needed to be done that “prevents, or at the very least slows down” Pakistan from “becoming a major Chinese outpost in Southwest Asia and the Indian Ocean basin regions”, Younus said.

“Should the crisis reach a point of no return for Pakistan, its leaders may accede to Chinese demands, leading to a dramatic increase in Beijing’s indolence in the region, including the Arabian Sea, the Himalayas, and onwards into Afghanistan and Central Asia”.