The Indigenous Voice “No” movement ran an aggressive campaign of disinformation. But it was the “Yes” side’s referendum to lose – and they did so, spectacularly. In terms of messaging and engagement, this was “one of the worst own-goals in democratic election history”, writes David Fedirchuk…

DAVID FEDIRCHUK

COMMENT

“The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place” — George Bernard Shaw

Last month, Australians voted in a referendum to amend the constitution to recognise Indigenous Australians with a body called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

This Voice would be an independent and permanent advisory body, giving advice to the Australian Parliament and Government on matters that affect the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

This was the fulfilment of an election campaign promise from prime minister Anthony Albanese, and what many considered an important step toward finally solving the painful and layered reality of Indigenous inequality across Australian society.

A year ago, in October 2022, polling showed the “Yes” side with a thirty five point lead over the “No” side, 67% to 32%. This seemed like a fait accompli for so many Australians, and like the marriage equality vote in 2017, it was well on its way to giving us a feel good fuzzy moment to temporarily distract us from the rising cost of living, overseas wars and climate change.

It only took about 90 minutes after polls closed on Saturday evening for the No side to declare victory.

The national tally (with compulsory voting) was clear: No at 61%, Yes at 39%. Yes failed in every state with Victoria’s 45% being its best showing.

A sad indictment on this country’s fractured population and an embarrassing look for Australia across the world, where once again we’re shown to be somewhat or completely divided, backward, racist and/or cruel.

Only the ACT recorded a majority “Yes” vote. Source: Supplied

So what went wrong? Brilliant organisation, funding and campaigning by the No side? Hardly. Lack of bipartisan support? It didn’t help, but in terms of messaging and engagement, this was one of the worst own-goals in democratic election history. It was the Yes side’s vote to lose, and they did so much to make that happen.

A few months out, referendum billboard, online and TV campaign ads started appearing with greater frequency. The No side came out with possibly the most cynical slogan since “Stop The Boats”. “If you don’t know, vote no”. Yuck. Essentially a call for ignorance, a juvenile condescending mantra from already unpopular and unelectable weasels like Peter Dutton and Clive Palmer.

Aka, the wrong side of history.

Mining billionaire Clive Palmer campaigned heavily against the Voice. Source: Clive Palmer/United Australia Party

For the Yes side this was in many ways a gift — how easy it would be to rise above that nonsense. They simply needed to address the three or so most repeated concerns of undecided (mostly older and rural) voters, essentially:

- What is the Voice?

- What powers will it have?

- Don’t we already have this in place?

Instead, what followed was a communications implosion of historical proportions where almost none of that was addressed. An amateurish, scattered, unorganised mishmash ensued which incredibly created more confusion and indecision, literally guiding voters to the No side.

“Instead, what followed was a communications implosion of historical proportions”

A cursory Google search for the Yes campaign in early September turned up no less than nine different campaign slogans: “Vote Yes”; “Together, for a better future”; “Recognition, listening and better results”; “Together we can make history”; “Vote Yes to that Voice Referendum thing”; “I’m voting Yes”; “Join us”, “Listen to your heart” and “History is calling”.

Yes23, the Labor Party, the Uluru Dialogue, Noel Pearson’s ‘From the Heart’, Damian Freeman’s ‘Uphold and Recognise’, the non-partisan Parliamentary friends of the Uluru statement and who knows how many others all seemed to be going in the same direction, and yet in completely different directions at the same time. So who’s responsible? Well, who’s in charge?

“A cursory Google search for the Yes campaign in early September turned up no less than nine different campaign slogans”

Back in June, Rachel Perkins, co-chair of Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition (AICR), and Dean Parkin, director of the AICR’s Yes23 campaign said: “The focus of the yes campaign would be on positive messaging and the benefits of the voice”.

Perkins said they wanted to offer an antidote to the “fear and misinformation” circulating in the community. Parkin added, “It is about ensuring people, no matter where they live, can get informed.” No mention of consistency, or any one, unified slogan.

Sitting on the AICR board is Mark Textor, a veteran pollster and strategist once described by Britain’s Channel 4 as “one of the most influential political strategists and pollsters to walk the planet”. Was his expertise not called on, or not listened to?

Uluru Dialogue Co-Chairs Pat Anderson AO and Professor Megan Davis must share the blame as well. As late as October 12, they asked undecided Aussies to ‘choose love over spin’. For those of you keeping score, that’s slogan number ten.

The October 14 referendum resulted in a strong “No” vote. Source: ABC News/Danielle Bonica

The fumbles kept coming as the Yes poll numbers plummeted. Incredibly, the first Yes television ads that appeared didn’t even mention the word ‘Voice’.

The Yes campaign was forced to delete a ‘confusing’ social media post showing an incorrect way to vote. At one stage the Yes side were warned by the Australian Electoral Commission for potentially misleading signs because they used the AEC’s distinct purple outside polling booths — all while slogan after slogan (after slogan) rolled out.

On top of this lack of any consistent messaging, they also released graphic design that seemed to be generated at random.

Same but different. Source: Supplied

Lack of resources were not an issue. The Yes side(s) had tens of thousands of volunteers, millions of dollars and reasoned, intelligent spokespeople with logic and the tenets of fairness and progression on their side.

They also had star power, with celebrities and their online presence ready to influence at scale.

What they didn’t seem to have were any communications or PR experts amongst all those warm bodies with extended job titles and honours — and this was clearly a fatal mistake. Anyone worth their salt could have cited ‘Kevin 07’, ‘Yes We Can’, ‘It’s Time’ or even ‘Make America Great Again’ for simple, consistent, memorable — and extremely successful campaign slogans.

A social media addicted public was ready for the hashtags, Tik Tok dances, Instagram story stickers and t-shirts — but there was no unity on what they would be.

Polls showed the confused and wary undecided voters were quickly becoming No voters, and by mid-July the Yes side slid below 50%, never to recover.

In the aftermath, the Yes side pointed to the No side’s misinformation tactics, the public’s entrenched racism and a lack of consultation with grassroots organisations. All convenient cop outs. Victorian Yes campaigner Marcus Stewart seemed to be one of the only people who really got it when he told ABC News the campaign, “struggled with our messaging and it got no cut through”. The understatement of the year.

Harvard’s Joe Slade White, the famous US political strategist wrote of the incredible importance in campaigns to “keep ads simple”.

‘Three points of simple straightforward information, delivered in a clear, and low key manner, can be the most effective way to set up a surge of voter movement”.

The US non-profit NGO The National Democratic Institute has a free handbook which also preaches, “Crafting and consistently using a compelling message is essential to persuading targeted voters to choose you”.

Washington University in St Louis agrees, with the seemingly obvious, “Research demonstrates importance of consistent branding in political television ads”.

All of this information is online — and free. And where was the in-house expertise that surely the Labor Party could (should?) have provided?

The incompetence is still difficult to believe.

They kept in simple back in the 1967 referendum on whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander should be included in official population counts. “Right Wrongs Write YES” cut through for over 90% of the national vote.

The 1967 “Yes” campaign kept it simple. Source: FCAATSI

The country that has never grown tired of, “Matter of fact, I’ve got it now”, “Lucky you’re with AAMI” and “There’s no other store like David Jones”, was ready to do the right thing, to get on board the Yes vote.

But a new “Come on Aussie” simply never appeared.

The problem is that — without sounding too cynical, there will not be another similar opportunity for Australia’s Indigenous population in our lifetimes. Like the botched 1999 Australian republic referendum, this was our one chance, and we blew it.

In an age where video, graphic and text messages can reach millions of people, in real time, essentially at no cost— somehow we blew it.

What a mess.

David Fedirchuk is writer, content creator and running addict who has worked across film, TV and corporate communications. Originally from Canada, he lives in Sydney. He can be reached at davidfedirchuk@gmail.com

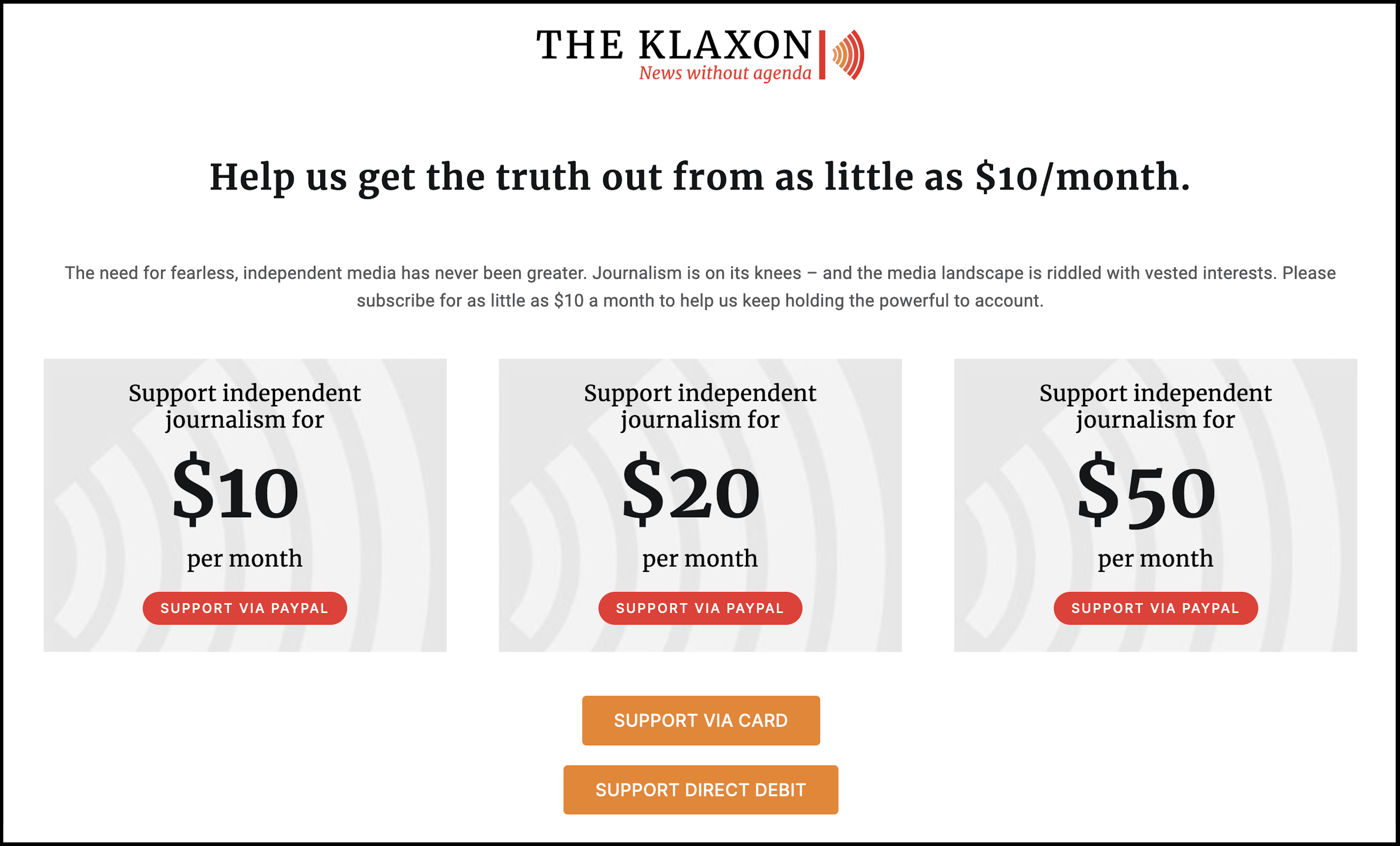

BEFORE YOU GO! Support truly independent journalism. Please SUBSCRIBE HERE or support us by making a DONATION. Thank you!

BEFORE YOU GO! Help us stay afloat and telling these stories. Please SUBSCRIBE HERE or support us by making a DONATION. Thank you!

Anthony Klan

Editor, The Klaxon

The Indigenous Voice “No” movement ran an aggressive campaign of disinformation. But it was the “Yes” side’s referendum to lose – and they did so, spectacularly. In terms of messaging and engagement, this was “one of the worst own-goals in democratic election history”, writes David Fedirchuk…

DAVID FEDIRCHUK

COMMENT

Last month, Australians voted in a referendum to amend the constitution to recognise Indigenous Australians with a body called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice.

This Voice would be an independent and permanent advisory body, giving advice to the Australian Parliament and Government on matters that affect the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

This was the fulfilment of an election campaign promise from prime minister Anthony Albanese, and what many considered an important step toward finally solving the painful and layered reality of Indigenous inequality across Australian society.

A year ago, in October 2022, polling showed the “Yes” side with a thirty five point lead over the “No” side, 67% to 32%. This seemed like a fait accompli for so many Australians, and like the marriage equality vote in 2017, it was well on its way to giving us a feel good fuzzy moment to temporarily distract us from the rising cost of living, overseas wars and climate change.

It only took about 90 minutes after polls closed on Saturday evening for the No side to declare victory.

The national tally (with compulsory voting) was clear: No at 61%, Yes at 39%. Yes failed in every state with Victoria’s 45% being its best showing.

A sad indictment on this country’s fractured population and an embarrassing look for Australia across the world, where once again we’re shown to be somewhat or completely divided, backward, racist and/or cruel.

Please support us by SUBSCRIBING HERE

Only the ACT recorded a majority “Yes” vote. Source: Supplied

So what went wrong? Brilliant organisation, funding and campaigning by the No side? Hardly. Lack of bipartisan support? It didn’t help, but in terms of messaging and engagement, this was one of the worst own-goals in democratic election history. It was the Yes side’s vote to lose, and they did so much to make that happen.

A few months out, referendum billboard, online and TV campaign ads started appearing with greater frequency. The No side came out with possibly the most cynical slogan since “Stop The Boats”. “If you don’t know, vote no”. Yuck. Essentially a call for ignorance, a juvenile condescending mantra from already unpopular and unelectable weasels like Peter Dutton and Clive Palmer.

Aka, the wrong side of history.

Mining billionaire Clive Palmer campaigned heavily against the Voice. Source: Clive Palmer/United Australia Party

For the Yes side this was in many ways a gift — how easy it would be to rise above that nonsense. They simply needed to address the three or so most repeated concerns of undecided (mostly older and rural) voters, essentially:

Instead, what followed was a communications implosion of historical proportions where almost none of that was addressed. An amateurish, scattered, unorganised mishmash ensued which incredibly created more confusion and indecision, literally guiding voters to the No side.

A cursory Google search for the Yes campaign in early September turned up no less than nine different campaign slogans: “Vote Yes”; “Together, for a better future”; “Recognition, listening and better results”; “Together we can make history”; “Vote Yes to that Voice Referendum thing”; “I’m voting Yes”; “Join us”, “Listen to your heart” and “History is calling”.

Yes23, the Labor Party, the Uluru Dialogue, Noel Pearson’s ‘From the Heart’, Damian Freeman’s ‘Uphold and Recognise’, the non-partisan Parliamentary friends of the Uluru statement and who knows how many others all seemed to be going in the same direction, and yet in completely different directions at the same time. So who’s responsible? Well, who’s in charge?

Back in June, Rachel Perkins, co-chair of Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition (AICR), and Dean Parkin, director of the AICR’s Yes23 campaign said: “The focus of the yes campaign would be on positive messaging and the benefits of the voice”.

Perkins said they wanted to offer an antidote to the “fear and misinformation” circulating in the community. Parkin added, “It is about ensuring people, no matter where they live, can get informed.” No mention of consistency, or any one, unified slogan.

Sitting on the AICR board is Mark Textor, a veteran pollster and strategist once described by Britain’s Channel 4 as “one of the most influential political strategists and pollsters to walk the planet”. Was his expertise not called on, or not listened to?

Uluru Dialogue Co-Chairs Pat Anderson AO and Professor Megan Davis must share the blame as well. As late as October 12, they asked undecided Aussies to ‘choose love over spin’. For those of you keeping score, that’s slogan number ten.

The October 14 referendum resulted in a strong “No” vote. Source: ABC News/Danielle Bonica

The fumbles kept coming as the Yes poll numbers plummeted. Incredibly, the first Yes television ads that appeared didn’t even mention the word ‘Voice’.

The Yes campaign was forced to delete a ‘confusing’ social media post showing an incorrect way to vote. At one stage the Yes side were warned by the Australian Electoral Commission for potentially misleading signs because they used the AEC’s distinct purple outside polling booths — all while slogan after slogan (after slogan) rolled out.

On top of this lack of any consistent messaging, they also released graphic design that seemed to be generated at random.

Same but different. Source: Supplied

Lack of resources were not an issue. The Yes side(s) had tens of thousands of volunteers, millions of dollars and reasoned, intelligent spokespeople with logic and the tenets of fairness and progression on their side.

They also had star power, with celebrities and their online presence ready to influence at scale.

What they didn’t seem to have were any communications or PR experts amongst all those warm bodies with extended job titles and honours — and this was clearly a fatal mistake. Anyone worth their salt could have cited ‘Kevin 07’, ‘Yes We Can’, ‘It’s Time’ or even ‘Make America Great Again’ for simple, consistent, memorable — and extremely successful campaign slogans.

A social media addicted public was ready for the hashtags, Tik Tok dances, Instagram story stickers and t-shirts — but there was no unity on what they would be.

Polls showed the confused and wary undecided voters were quickly becoming No voters, and by mid-July the Yes side slid below 50%, never to recover.

In the aftermath, the Yes side pointed to the No side’s misinformation tactics, the public’s entrenched racism and a lack of consultation with grassroots organisations. All convenient cop outs. Victorian Yes campaigner Marcus Stewart seemed to be one of the only people who really got it when he told ABC News the campaign, “struggled with our messaging and it got no cut through”. The understatement of the year.

Harvard’s Joe Slade White, the famous US political strategist wrote of the incredible importance in campaigns to “keep ads simple”.

‘Three points of simple straightforward information, delivered in a clear, and low key manner, can be the most effective way to set up a surge of voter movement”.

The US non-profit NGO The National Democratic Institute has a free handbook which also preaches, “Crafting and consistently using a compelling message is essential to persuading targeted voters to choose you”.

Washington University in St Louis agrees, with the seemingly obvious, “Research demonstrates importance of consistent branding in political television ads”.

All of this information is online — and free. And where was the in-house expertise that surely the Labor Party could (should?) have provided?

The incompetence is still difficult to believe.

They kept in simple back in the 1967 referendum on whether Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander should be included in official population counts. “Right Wrongs Write YES” cut through for over 90% of the national vote.

The 1967 “Yes” campaign kept it simple. Source: FCAATSI

The country that has never grown tired of, “Matter of fact, I’ve got it now”, “Lucky you’re with AAMI” and “There’s no other store like David Jones”, was ready to do the right thing, to get on board the Yes vote.

But a new “Come on Aussie” simply never appeared.

The problem is that — without sounding too cynical, there will not be another similar opportunity for Australia’s Indigenous population in our lifetimes. Like the botched 1999 Australian republic referendum, this was our one chance, and we blew it.

In an age where video, graphic and text messages can reach millions of people, in real time, essentially at no cost— somehow we blew it.

What a mess.

David Fedirchuk is writer, content creator and running addict who has worked across film, TV and corporate communications. Originally from Canada, he lives in Sydney. He can be reached at davidfedirchuk@gmail.com

BEFORE YOU GO! Support truly independent journalism. Please SUBSCRIBE HERE or support us by making a DONATION. Thank you!

BEFORE YOU GO! Help us stay afloat and telling these stories. Please SUBSCRIBE HERE or support us by making a DONATION. Thank you!

Anthony Klan

Editor, The Klaxon

Related Posts

KPMG CEO Andrew Yates: The “Barnaby Joyce of Big Audit”

COMMENT: Almost 700 deaths. Zero heads have rolled. Why?