The string of key officials closest to the scandal that cost the jobs of the top two bosses at corporate regulator ASIC refuse to back Treasurer Frydenberg’s unsubstantiated claims that no wrongdoing occurred. It’s been revealed that three-quarters of the key findings made by the investigation into corruption at ASIC have been secretly deleted – and Josh Frydenberg’s been deserted. Anthony Klan reports.

Appreciate our quality journalism? Please donate here

EXCLUSIVE

Australia’s most senior Treasury official – and the entire new management at the corporate regulator – have refused to back Josh Frydenberg’s claim that the investigation into corruption at the top of the regulator found no wrongdoing.

Secretary to the Australian Treasury Dr Stephen Kennedy, who reports directly to Frydenberg, has distanced himself from the Treasurer, declining to stand by claims that no wrongdoing occurred at the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC).

It can also be revealed that ASIC’s entire new senior executive, now under new chair Joe Longo, has also refused to back up Frydenberg’s claims about the scandal, which saw ASIC’s two top executives lose their jobs.

Both Kennedy and Longo report directly to Treasurer Frydenberg.

Kennedy, a highly-regarded senior public servant, has repeatedly declined to comment when formally asked whether he agreed with Frydenberg’s claim that no wrongdoing had occurred at the top of ASIC.

Instead, we were directed to a statement that contains only the unsubstantiated claims from Frydenberg himself.

Secretary to the Treasury Kennedy is a long-time public servant with a respectable track-record.

His refusal to stand by Frydenberg’s claims is particularly significant given it was Kennedy himself who both legally commissioned the ASIC review and approved its $110,000 cost.

On October 23 it emerged that then ASIC chair James Shipton and deputy chair, Daniel Crennan QC, had received $188,178 in “relocation” payments, above the “total remuneration” they were legally allowed.

(Those limits are set each year by the government Remuneration Tribunal.)

In other words, the salary caps of both men had been substantially breached.

It’s the biggest scandal in ASIC’s 30-year history.

Shipton had received $118,557 in personal “tax advice”, while ASIC had been paying $500 a week rent towards the rent of Crennan’s luxury Sydney family home, totalling $69,621 over more than 18 months.

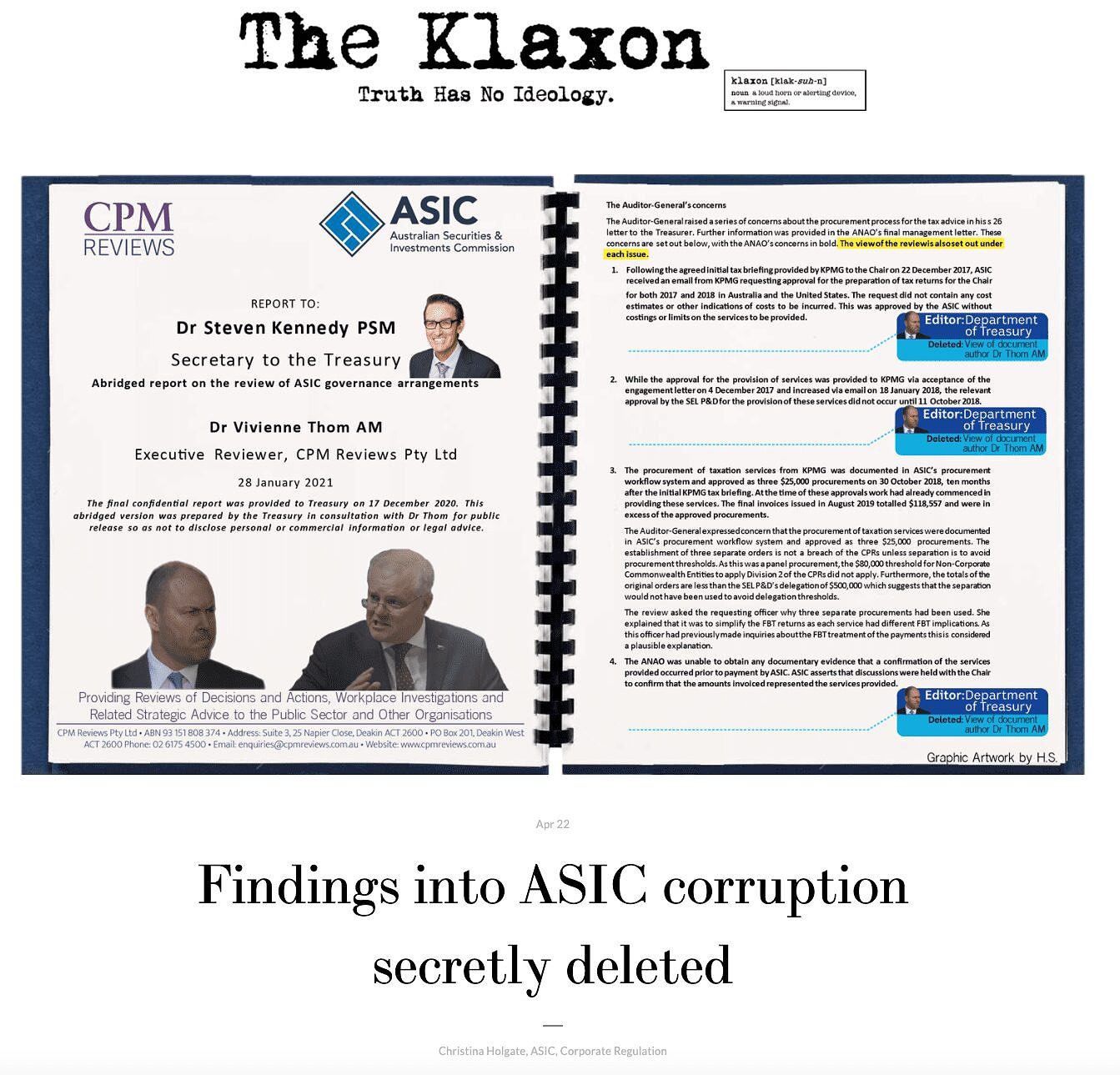

The Klaxon’s April 22 expose. Source: The Klaxon

At the same time as he disclosed the ASIC scandal, on October 23, Frydenberg announced an investigation would be conducted by former senior public servant, Dr Vivienne Thom.

Thom was previously Australia’s federal Inspector-General of Intelligence, where she was responsible for the oversight of six of the nation’s key intelligence agencies.

On January 29 Frydenberg released a version of Thom’s report from which, as revealed by the The Klaxon, three of the four key findings have been secretly deleted.

On releasing the doctored document, Frydenberg made the unsubstantiated claims that Thom’s report contained no evidence of any wrongdoing by Shipton or Crennan.

Thom resigned immediately afterwards.

The Treasurer’s unsubstantiated claims are despite the Shipton “tax advice” payments being over 60-times the legal limit; that Crennan himself has admitted the $69,621 payments from ASIC towards his rent were illegal from the outset; and that Shipton and Crennan repaid the $188,178 – though only after unprecedented anti-corruption action by Australia’s Auditor-General.

Frydenberg’s unsubstantiated claims are also despite both Shipton and Crennan losing their jobs in the scandal, barely half-way through their five-year terms at the helm of Australia’s corporate corruption regulator.

The doctored, “abridged”, version of Thom’s report re-written by Treasury. Source: Treasury

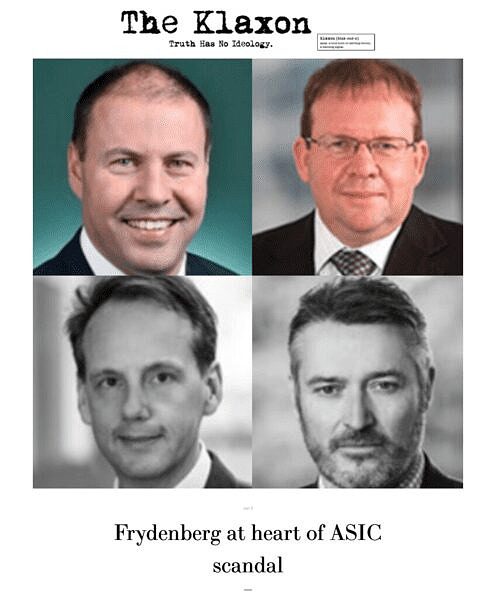

The latest revelations mean that the company contracted to undertake the review (CPM Reviews); the review’s author (Thom); the head of Australia’s Treasury (Kennedy); and each of the six commissioners now in charge of the nation’s corporate regulator ASIC (new chair Joe Longo, deputy chairs Karen Chester and Sarah Court, and commissioners Cathie Armour, Sean Hughes and Danielle Press), have all refused to stand by Frydenberg’s claims that no wrongdoing occurred.

Frydenberg himself has provided no evidence to back his claims, other than producing the doctored document itself.

In fact, the only official to have made the claim – anywhere, anytime – that Thom found no wrongdoing, is Frydenberg.

The Klaxon has been unable to find a single other government MP, agency official or government legal officer of any kind who will corroborate the Treasurer’s claims.

Frydenberg has never denied doctoring the document, or of having the document doctored on his behalf, despite repeated approaches by this publication.

Frydenberg has also repeatedly refused to disclosed what the precise “terms of reference” were set for the inquiry.

In other words, he won’t say what the instructions were given to CPM Reviews.

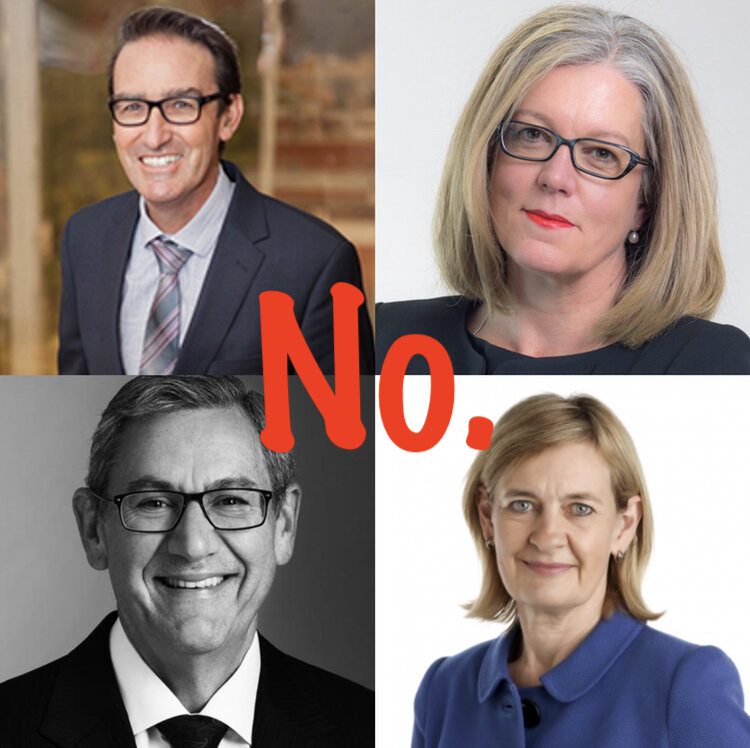

All key officials are refusing to back Frydenberg’s claims. Clockwise from top left: Stephen Kennedy, Karen Chester, Sarah Court and Joe Longo.

This week Treasurer Frydenberg conducted a media blitz this week, giving over a dozen TV and radio interviews.

Remarkably, Frydenberg was not asked about his secret doctoring of the findings of Thom’s investigation into corruption at the top of ASIC, the corporate corruption regulator.

Frydenberg also had “opinion” pieces published in Sydney’s Daily Telegraph and Melbourne’s Herald Sun.

Frydenberg’s media blitz over the past five days:

Treasurer Frydenberg’s media blitz since Tuesday. Source: Twitter

Intelligence

As Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security, Thom was responsible for overseeing and monitoring the activities of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) and three other intelligence agencies.

It is an extremely important position, right at the heart of Australia’s national security.

After her five-year term expired in 2015, Thom joined private Canberra-based investigations company CPM Reviews.

When Frydenberg announced on October 23 that Thom would be conducting the ASIC investigation, it was in her capacity as a senior investigator at CPM Reviews.

Thom handed her ASIC report to the government on December 17.

Frydenberg has never released it.

Instead, on January 29, six weeks later, Frydenberg released a doctored version.

As revealed by The Klaxon, three of the report’s four key findings have been secretly deleted.

The only response that was not deleted relates to a matter where no specific wrongdoing was identified by Thom.

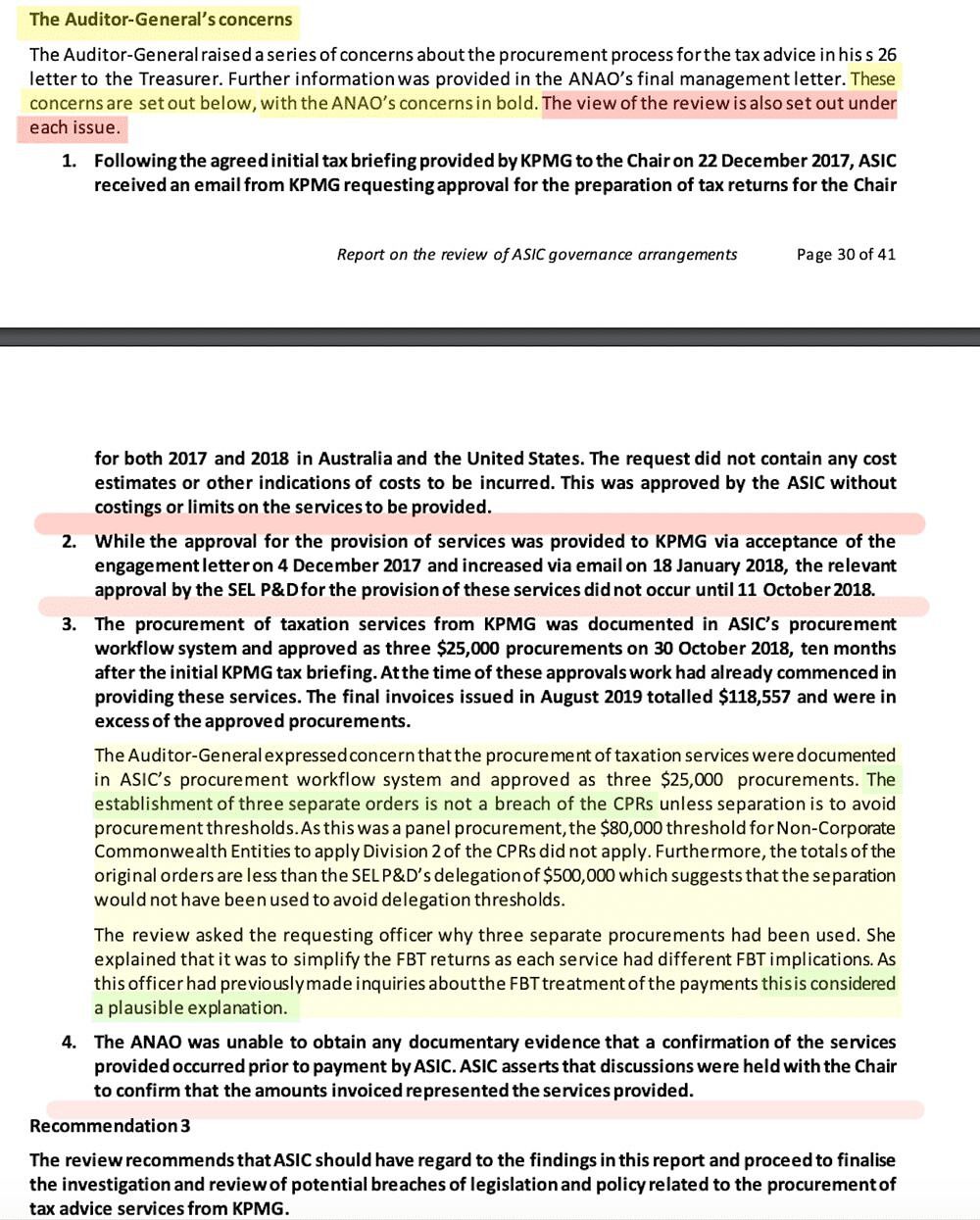

The secretive doctoring occurs on pages 30-31 of the document.

It is indisputable and clearly apparent.

The “view of the review” is “set out under each issue”.

Only it’s not.

The responses to three of the four serious concerns, that were raised with Frydenberg by the Auditor-General, the nation’s chief auditor, have been deleted entirely.

The red lines are where those missing key findings should be.

Pages 30 and 31 of Frydenberg’s doctored version of the Thom report, deletions shown in red. Source: Treasury. Emphasis: The Klaxon

Frydenberg released the doctored document on January 29.

Despite providing no evidence to back the claim – other than the doctored document itself – Frydenberg simultaneously announced: “Dr Thom made no adverse findings against Mr Shipton and Mr Crennan”.

Despite Thom clearly indicating that further legal and regulatory action against Shipton was required (Thom even identifies the specific laws and codes of conduct which Shipton has almost certainly broken) Frydenberg simply declared Shipton had done nothing wrong.

“I am satisfied that there have been no instances of misconduct by Mr Shipton,” he announced.

Again, other than providing the doctored document itself, Frydenberg has provided no evidence to back-up that claim, despite our repeated requests.

CPM Reviews – among the many refusing to back Frydenberg’s claims. Source: The Klaxon

Frydenberg made the claims despite, at the same time, also announcing that Shipton would go and that “Treasury will immediately commence a search process for a new Chairperson”.

Shipton, who “stood down” as ASIC chair when the scandal broke on October 23, was just three years in to his five-year term.

Thom resigned from CPM Reviews, where she had worked in senior roles for over four years, immediately after Frydenberg made the unsubstantiated claims.

Thom has repeatedly declined to comment.

Employees in roles such as Thom’s position at CPM Reviews, are often required to sign “confidentiality” clauses in relation to their work.

CPM Reviews itself has also refused to back up Treasurer’s claims.

It has repeatedly refused to back-up Frydenberg’s claims about the contents of its ASIC review when contacted by The Klaxon.

Record breaking

The matter is extremely serious.

Not only does the issue involved alleged serious corruption at the top of the corporate corruption regulator – and an apparent subsequent cover-up by Australia’s Treasurer – the entire matter only emerged at all because of an unprecedented intervention by the nation’s Auditor-General.

In October, Australia’s chief auditor, Auditor-General Grant Hehir, formally issued Treasurer Frydenberg with a so-called “section-26” anti-corruption notice.

According to experts, it is the only time a section-26 notice has been issued in Australian history.

Provided for under the Auditor-General Act (1997), the Auditor-General is required to bring to the attention of the relevant minister “any matter that, in the Auditor‑General’s opinion, is important enough to justify it being brought to the attention of the responsible Minister”.

Hehir issuing the notice meant the ASIC salary cap scandal could not longer be hidden from the public – it forced Frydenberg to disclose it.

The Klaxon’s January 1 expose. Source: The Klaxon

Hehir was deeply concerned that there was an ongoing cover-up taking place.

His agency, the Australian National Audit Office, had been formally raising its serious concerns about the salary cap breaches with ASIC for 18 months.

Yet Shipton’s ASIC – and Treasurer Frydenberg – had consistently refused to take action.

Frydenberg disclosed the ASIC scandal on October 23.

The afternoon before, Prime Minister Scott Morrison had “thrown under the bus” Australia Post CEO Christina Holgate, aggressively attacking her in Federal Parliament despite providing no evidence of any wrongdoing.

Holgate was subsequently cleared of any wrongdoing whatsoever.

Yet Morrison’s attacks on Holgate in Federal Parliament on the afternoon of October 22 – followed up by other Coalition MPs that evening – meant that, predictably, the fabricated Holgate “scandal” vastly overshadowed the much bigger scandal at ASIC announced the next day.

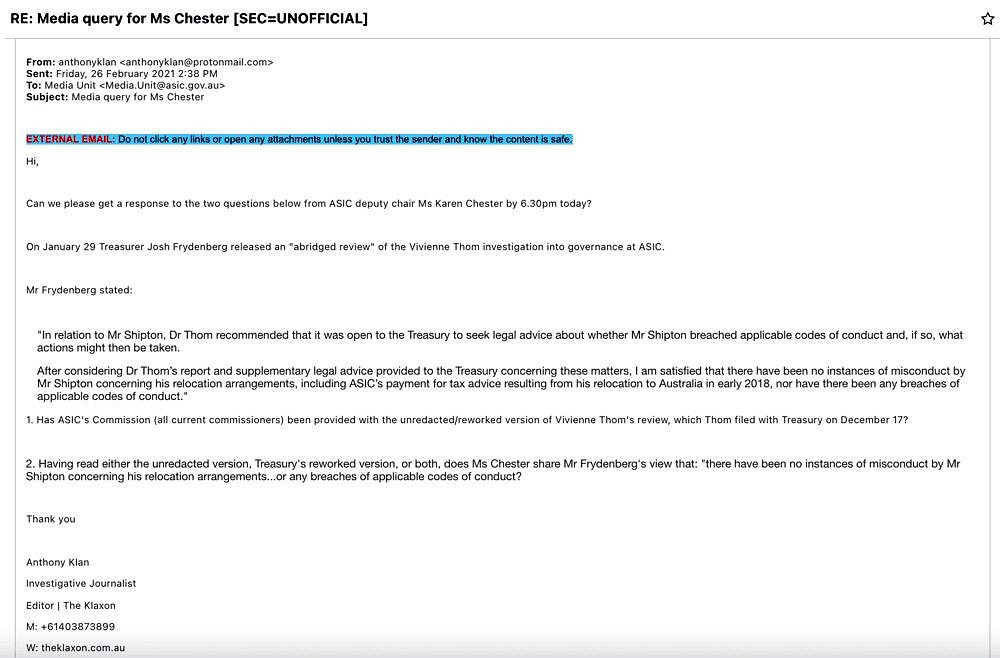

As previously revealed, ASIC deputy chair Karen Chester has repeatedly refused to stand by Frydenberg’s claims that no wrongdoing occurred at the top of the regulator.

In February and March, before Longo replaced Shipton as ASIC boss, Chester was the most senior official at ASIC not directly implicated in the salary cap scandal.

We approached Chester on February 26. We asked, whether having read either Thom’s un-redacted final report, or the doctored version that Frydenberg released, whether Chester shared Frydenberg’s view.

That is, whether “there have been no instances of misconduct by Mr Shipton concerning his relocation payments…or any breaches of applicable codes of conduct”.

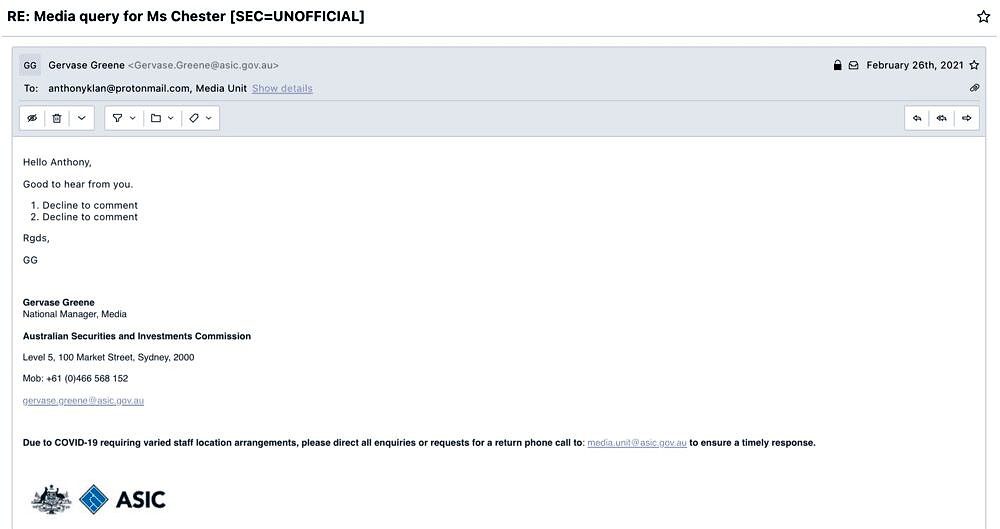

Chester’s response, provided through ASIC national media manager Gervase Green, was succinct:

“2. Decline to comment”

The current, ongoing, refusal by the entire ASIC “Commission”, which now includes Longo as chair and Sarah Court as deputy chair, to stand by Frydenberg’s unsubstantiated claims is also highly illuminating.

That’s even more the case because it was Frydenberg himself who appointed Long and Court.

(The pair started at ASIC on April 1. ASIC has two deputy chairs, Court and Chester).

Aside from potential serious reputational damage were they to stand by Frydenberg’s claims, if those claims turned out to be false, the heads of government agencies, which include the Treasury Secretary (Kennedy) and the chair of ASIC (Longo) are bound by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act).

The PGPA Act is about “governance, performance and accountability” and requires department heads to “manage public resources properly”.

(This is the same legislation that helped cost ASIC boss Shipton his job).

By claiming the contents of the ASIC investigation found no wrongdoing, if this was untrue, Kennedy could potentially be in breach of the law.

The ASIC “review” involved handing a substantial amount of taxpayer money to a private company for a service, with the transaction authorised by Kennedy.

The review arguably could have worth, that is, value for taxpayers, whether it is released publicly or not.

But it has zero worth – in fact substantial negative worth – if the review found one thing, and Kennedy, at a $110,000 cost to taxpayers, told the public it contained another.

It’s one thing for a government official to commission a report and not release it. It’s another entirely another for an official to commission a report and then allegedly lie about its contents.

Kennedy has repeatedly declined to stand by Frydenberg’s comments.

In a carefully-worded response, Kennedy’s office told us it had nothing to “add” to Frydenberg’s statement of January 29.

That January 29 statement was made solely by Frydenberg and he is 100% responsible for its contents.

More to come.