The “independent review” into the corruption at ASIC is a sham. Having sat on it for six weeks, Josh Frydenberg released an altered, re-worked version on January 29. ASIC chair James Shipton would resign – but Frydenberg claimed the review made “no findings of wrongdoing” and that he, as Treasurer, was “satisfied” that no wrongdoing had ever occurred. This goes against all available evidence – even against the evidence of Frydenberg’s altered report. The Vivienne Thom review was a stitch-up from the outset. Frydenberg has full control of the scandal once more – and he’s announced there’s nothing to see here. It’s a cover-up of the cover-up of corporate corruption at the top of the corporate corruption regulator. Anthony Klan investigates.

Appreciate our quality journalism? Please donate here

EXCLUSIVE

The Federal Government’s “independent review” into corruption at the corporate regulator was a sham from the outset, with Treasurer Josh Frydenberg issuing it with secret instructions that ensured it would never make a single “finding” of illegality or wrongdoing, regardless of what it actually uncovered.

Frydenberg on January 29 announced that he had received the findings of his “review” into the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, and that it had made “no adverse findings” against either ASIC chairman James Shipton or former ASIC deputy chairman Daniel Crennan QC.

That claim is despite the review itself containing key evidence that the $118,557 ASIC paid for Shipton’s personal “tax advice” was more than 60 times the legal limit.

It’s also despite the review itself providing highly-detailed evidence proving – unquestionably – that payments by ASIC of $750 a week towards the rent on Crennan’s luxury Sydney home, almost $70,000 in all, were illegal from the outset.

Frydenberg has refused to release the final report of the “review”, which he has described as being “independent” despite it being conducted by his appointee, investigator Vivienne Thom, and it having been conducted through the Department of Treasury, which he oversees.

Instead, when Frydenberg broke his three-month silence on the ASIC scandal on January 29, he released a 41-page “abridged” version of Thom’s final report.

It emerged Frydenberg had been sitting on Thom’s final report since December 17.

The 41-page document he released on January 29 has been altered and reworked by Frydenberg’s Department of Treasury.

“Frydenberg’s claim is despite key evidence showing Shipton’s $118,557 ‘tax advice’ was more than 60 times the legal limit”

The document, which discloses having been “produced by Treasury”, is dated January 28, which is six weeks after Thom submitted her final report.

Neither Treasury or Frydenberg – or anyone else – has disclosed what specific changes were made, what information was removed, or how many alterations were conducted.

However Treasury’s 41-page document does reveal that the Thom review didn’t even fully complete the central investigation into the $118,557 Shipton payments – instead simply putting the matter back to ASIC itself.

It states: “ASIC should…proceed to finalise the investigation” into “potential breaches of legislation related to the procurement of tax advice services from KPMG”.

ASIC, like Treasury, is overseen by Frydenberg.

Despite it being an “abridged” version, the 41-page document contains clear evidence that both the Shipton and Crennan payments were illegal.

Stitched-up: Australian media outlets falsely report that Frydenberg’s review “clears” ASIC chair James Shipton of wrongdoing. This is entirely incorrect. Source: Supplied

Frydenberg has repeatedly, over several months, refused to comment when asked by The Klaxon what specific “terms of reference” – or parameters of inquiry – he set for the Thom review.

Close examination of Treasury’s 41-page “abridged” document reveals, for the first time, what they were.

Frydenberg announced the Thom review on October 23, but only after Auditor-General Grant Hehir took extremely rare action and issued a “section 26” letter, which forced the ASIC scandal to be made public.

By then, the review also reveals, ASIC and Frydenberg’s Treasury – which are now both back in full control of the affair – had been taking actions that prevented the matter from being publicly exposed for at least 14 months.

The Klaxon can now exclusively reveal that Frydenberg tasked the Thom review with simply making “findings of fact” – not with determining whether or not any illegality or other wrongdoing had actually occurred.

In other words, its job was to simply establish the specifics, the evidence, about what happened and when regarding the Shipton and Crennan payments.

“ASIC should…proceed to finalise the investigation”

— Vivienne Thom “review”

Detailed analysis of the 41-page document reveals that the Thom review made “no adverse findings”, not against Shipton, Crennan – or anyone else – because doing so was never part of the secret remit that Frydenberg gave it.

The document also confirms The Klaxon’s January 1 expose: the Thom review failed to take the simple, fundamental step of actually asking the Remuneration Tribunal – the relevant body under Australian law – whether the Shipton and Crennan payments were legal.

That fundamental flaw makes a transparent sham of Frydenberg’s “independent review”, even before any other considerations.

But further, highly-detailed, analysis by The Klaxon reveals the ASIC affair – the biggest corporate governance scandal in decades – is wider, more complex, and even more serious than was previously known.

On January 29, Frydenberg, highly misleadingly, announced that: “Dr Thom made no adverse findings regarding Mr Shipton and Mr Crennan”.

Almost every major Australian media outlet then falsely reported that the Thom review had “cleared” Shipton and Crennan of wrongdoing.

This is not true.

The 41-page abridged review makes no such findings.

In fact, all the available evidence points to the exact opposite.

It reveals:

- Shipton admits he failed to recuse himself from overseeing the scandal that he was at the centre of, even after being expressly told by ASIC’s own auditor that his $118,557 “tax advice” benefits were illegal

- Shipton and others, including several key ASIC executives, have almost certainly broken a string of serious laws but are avoiding accountability

- The $118,557 in personal “tax advice” provided to Shipton was over 60 times more than the legal amount, according to ASIC’s own auditor

- Shipton has remarkably claimed he is not bound by ASIC’s own Code of Conduct – which he co-wrote – because he didn’t agree to it in his employment contract

- Shipton was given a copy of Frydenberg’s “independent review” before it was completed to “provide comment”

- Shipton allegedly kept the $118,557 “tax advice” matter from ASIC’s “commission”, its small group of key executives

- The $70,000 payments towards Crennan’s rent were outright illegal from day one

- Claims by ASIC that it had made the payments because Crennan had been been “required” to relocate for work were untrue

- ASIC has failed to provide a valid reason as to why it failed to take adequate action over the scandal despite repeated and serious official warnings over at least 14 months

- ASIC has failed to provide a valid reason why (it claims) it never took the simple step of approaching the government Remuneration Tribunal to see whether or not the Shipton and Crennan payments were legal

- The specific “terms of reference” of the Thom review – set by Frydenberg, who has repeatedly refused to disclose them – were manipulated so it would never “find” any wrongdoing, facilitating the ongoing cover-up

Frydenberg

The Thom review provides large amounts of evidence exposing serious illegality and widespread improper behaviour, including strong evidence of serious wrongdoing by both Shipton and Crennan.

It makes clear the Shipton and Crennan payments were illegal – even despite the review itself openly admitting it hasn’t fully completed the Shipton investigation, which it has now passed to ASIC.

How The Klaxon broke the story: Both Frydenberg and Thom’s “independent review” refuse to simply ask Remuneration Tribunal Source: The Klaxon

Under the parameters of engagement that Frydenberg set for it, the Thom review doesn’t technically make “findings” of wrongdoing, yet it has fulfilled its task in delivering “findings of fact” and providing “advice” on those findings.

At the bottom of page 35, the abridged document states: “The terms of reference of this review require advice on findings of fact with a view to providing a basis for legal advice concerning the next steps available”.

(It’s the only place in the 41-page document that this full disclosure is made.)

That “advice” from Thom is that ASIC and Treasury should now take action.

But on Friday January 29, Frydenberg – who is responsible for both ASIC and Treasury – announced, despite providing zero evidence, that he had given Shipton the all-clear.

Despite the extremely serious situation – corporate corruption at the top of the corporate corruption regulator – the Federal Treasurer strongly doubled down on the stitch-up he had seeded at the heart of the Thom review back in October.

While simultaneously announcing that Shipton would be replaced as ASIC Chair in the coming three months – little over halfway into his five-year term – Frydenberg on January 29 announced that he was “satisfied” Shipton had engaged in no wrongdoing whatsoever.

“After considering Dr Thom’s report and supplementary legal advice provided to the Treasury concerning these matters, I am satisfied that there have been no instances of misconduct by Mr Shipton concerning his relocation arrangements, including ASIC’s payment for tax advice resulting from his relocation to Australia in early 2018, nor have there been any breaches of applicable codes of conduct,” Frydenberg states.

He provided zero evidence to support this.

Close analysis of the document released by Treasury reveals the opposite is true.

The Thom review has provided Frydenberg, Treasury and ASIC with large amounts of evidence exposing serious illegality and widespread improper behaviour, it just doesn’t – technically – make any “adverse findings” against Shipton and Crennan.

Frydenberg’s 41-page “abridged version” of Dr Vivienne Thom’s review. Source: Department of Treasury

The 41-page “abridged version” of Thom’s final report is a highly unusual document.

For example, on page 19, regarding the Crennan payments, is the bold subheading:

“5. WERE THE RENTAL ALLOWANCE PAYMENTS MADE WITH APPROPRIATE AUTHORISATION AND IN ACCORDANCE WITH ALL LEGISLATIVE POLICY AND PROCEDURAL REQUIREMENTS?”

But it doesn’t actually provide a direct answer to that key question.

Similarly, on page 27, regarding the Shipton payments, is the bold subheading:

“7. WERE THE TAX ADVICE PAYMENTS MADE WITH APPROPRIATE AUTHORISATION AND IN ACCORDANCE WITH ALL LEGISLATIVE POLICY AND PROCEDURAL REQUIREMENTS?”

Again, it doesn’t actually provide a direct answer to the question.

That’s despite the entire ASIC scandal being about those Shipton and Crennan payments.

SCOOP: ASIC’s “internal audits” run KPMG, the same group that charged ASIC $118,557 for Shipton’s “tax advice”. Source: The Klaxon

Yet while the document fails to specifically “find” whether or not the Shipton and Crennan payments were legal, it provides detailed evidence which shows they clearly weren’t.

Not from the outset.

It shows that ASIC’s own auditor, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) – which had warned ASIC in August 2019 that the Crennan payments were likely illegal – expressly told ASIC in August last year, a year later, that the Shipton payments were illegal.

(The ANAO is overseen by Auditor-General Grant Hehir).

Yet despite being informed of this on August 11, Shipton remained in charge of “overseeing the ANAO’s concerns” despite those concerns being specifically about him and his actions.

The way the final review is structured (or as it is presented in the abridged version, at least) Thom provides her “findings of fact”.

Those “findings of fact” are the evidence – ie. simply what happened and when.

Next to that evidence, Thom points to numerous specific laws and policies.

Most, if not all, of those laws and policies that Thom lists have clearly been broken.

Crennan

Daniel Crennan QC was appointed ASIC deputy chair under Treasurer Josh Frydenberg in July 2018.

He was living in a luxury rental property in Melbourne’s Brighton at the time.

“He was to be based in Melbourne,” Thom states regarding Crennan’s appointment.

Shortly afterwards, Peter Kell, who at the time had also been ASIC’s Deputy Chair, and who was based in Sydney, “resigned unexpectedly”.

“Mr Crennan and the ASIC chair (Shipton)…agreed it would be preferable to have a Deputy Chair based in Sydney,” Thom states.

However despite ASIC repeatedly – and formally – claiming otherwise, Thom says “there was no evidence to suggest that he (Crennan) was directed to move”.

“Another member could have been requested to move or ASIC could have continued under the existing arrangements,” Thom states.

Regardless, Crennan moved to Sydney with his family.

The Thom review states that the relevant “People and Development” officer at ASIC (who Thom interviewed as part of her investigations), “record(s) that Mr Crennan was ‘keen to receive some sort form of rent assistance’.”

Although Crennan denies having said this to the officer, ASIC then agreed to pay $750 a week towards Crennan’s Sydney rent for two years, from January 5, 2019.

In early August 2019, seven months in, the ANAO told ASIC the payments were likely illegal and ASIC should seek adjudication from the relevant body, the Remuneration Tribunal.

Despite being pushed by the ANAO for over a year – 14 months – ASIC, according to the Thom review, never sought a firm finding from the Remuneration Tribunal.

Providing such information is part of the Remuneration Tribunal’s job.

This role is clearly stated in the Remuneration Tribunal Act 1973, as well as on the Remuneration Tribunal’s website.

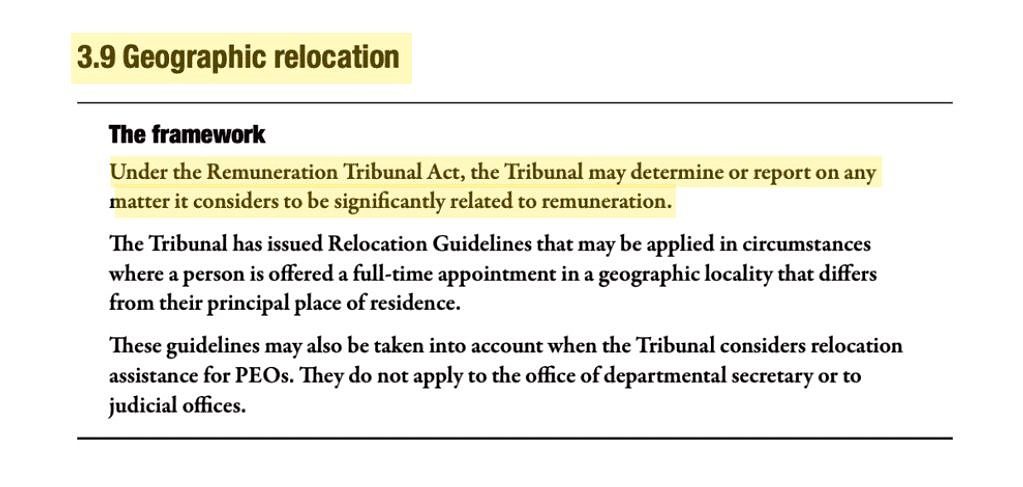

Its latest annual report, under the heading “Geographic relocation” the Remuneration Tribunal states it may “report on any matter it considers to be significantly related to remuneration”.

Remuneration Tribunal: can report on “any matter related to remuneration”. Source: Remuneration Tribunal Annual Report 2019-20

ASIC continued making the $750 a week payments until September last year, when Crennan announced he would repay the money “as a debt to the Commonwealth”.

That was after it became apparent that ASIC would be forced – by law, and enforced by the ANAO – to reveal the improper payments publicly.

Crennan resigned weeks later, when the scandal became public in October.

He was less than half-way in to his five-year term.

In the 41-page document, Thom does not technically make “findings” that the Crennan payments were illegal or even improper.

Yet the fact that they were illegal from day one is not disputed.

The Remuneration Tribunal’s “Guidelines on Geographic Relocation Of Full Time Office Holders” states: “Reimbursement of relocation costs will only continue while:

- the office holder continues to have a property in their home locality, as their principal place of residence”

At no time was it ever suggested that Crennan would keep a “principal place of residence” in Melbourne, so the law was transparently broken from the outset.

The fact that the payments were clearly all illegal is reflected in statements from Crennan himself to Thom during her interview process: “I offered to pay it back on the basis that it was a debt to the Commonwealth”, Crennan says.

“ASIC…hadn’t taken into consideration the Remuneration Tribunal determination (relevant law) and therefore the debt arose from me to the Commonwealth”.

Shipton

Regarding ASIC chair James Shipton, Thom lists a host of very specific laws “in connection with this review”.

Almost all – if not all – appear to have certainly been broken.

For example, Thom cites the Remuneration Tribunal Act 1993, which has clearly been broken.

The Remuneration Tribunal, under legislation, each year sets the “total remuneration” that is to be paid to federal politicians and key public officials – including the chair and deputy chair of ASIC.

The law states that the ASIC chairman was to receive “total remuneration” of $775,910 in 2019-20.

The $118,557 ASIC paid KPMG for Shipton’s personal “tax advice” was above this.

“Achieving our Vision depends on the integrity of our people”

— James Shipton, ASIC Code of Conduct

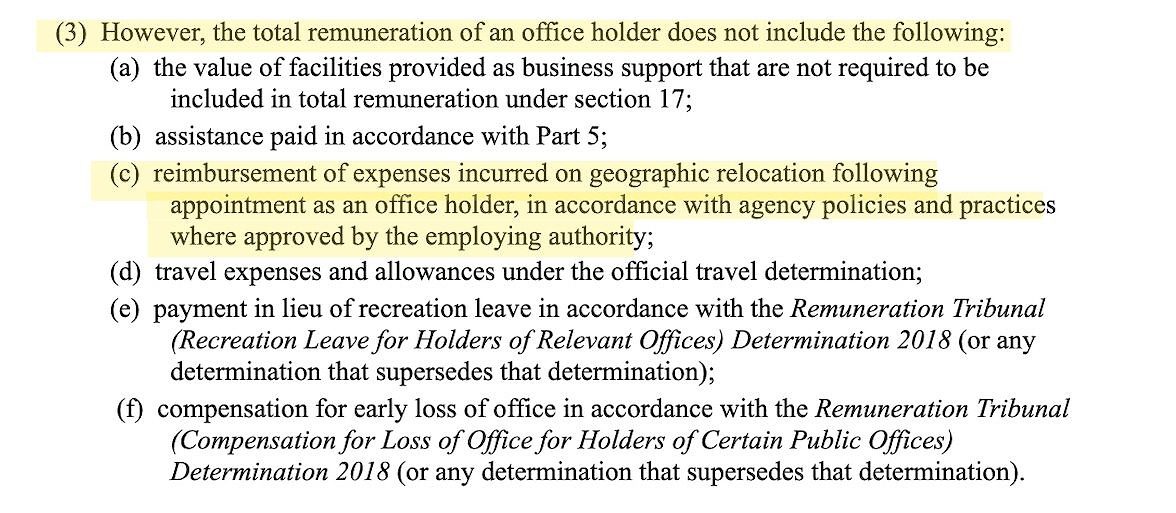

Shipton’s ASIC has long argued – since at least August 2019 – that the payments to Shipton and Crennan were legal because they were “relocation expenses”.

One exception under the Remuneration Tribunal’s rules is that reimbursements made for legitimate “relocation expenses” can be on top of the legislated “total remuneration” cap.

That’s because legitimate relocation expenses would be a work expense, rather than benefits to the employee as an individual.

This exception only applies regarding “reimbursement of expenses” incurred on “geographic relocation”; occurring “following appointment as an officeholder”; where the expenses have been “approved by the employing authority”; and where all those payments are “in accordance with agency policies and practices”.

The Remuneration Tribunal Act 1973. Source: Australian Government

Further, the Remuneration Tribunal, in its relevant “Guidelines on Geographical Relocation” states the costs must be “reasonable”.

Relocation costs must be “reasonable”: Part of the two-page Remuneration Tribunal Guidelines on Geographical Relocation relocation, issued in December 2014. Source: Remuneration Tribunal.

Having repeatedly raised serious concerns with ASIC over the $118,557 Shipton payment since at least August 2019, in August last year the ANAO told ASIC that all but about $2,000 of them were illegal.

The only legitimate expense was for an “initial tax advice” session, of up to two hours, which Shipton had received from KPMG on December 22 2017 at a “total cost” of $1917.

Additional costs, which included numerous items, among them the completion of three years of Shipton’s personal tax returns, were not legal.

The $118,557 paid by ASIC was 62 times the legally allowed $1917, “initial tax advice”.

Thom, again does not make “findings”.

Remuneration Tribunal claims it has “no record” of ASIC seeking advice over legality of Crennan payments. Yet internal ASIC documents claim it did. Source: The Klaxon

But she notes that even if the three Shipton tax returns were included, the “reasonable” cost would still only have been a maximum of “up to” $11,750, plus the $1917 cost of the initial briefing.

That’s a total “reasonable” cost of just $13,667.

The 41-page document proves that Shipton was formally told the ANAO position – ie that almost of all of the “tax advice” benefits to him were illegal – on August 11 last year.

It shows the ANAO had said, in writing, that the “real crux of the issue” was that: “with the exception of the initial tax advice, the payments made for other taxation support and advice do not meet the definition of a relocation expense and have resulted in the (Remuneration) Tribunal Determination being exceeded”.

“This is considered a breach of the Remuneration Tribunal Act”.

Shipton failed to removed himself “from the management of the ANAO’s concerns about the payments for the tax advice”, Thom states, despite Shipton having been alerted to “those concerns on 11 August 2020”.

While she does not technically “find” any wrongdoing, the situation presents a clear, and very serious conflict of interest.

Thom states: “Mr Shipton may reasonably be seen to have had a personal responsibility for disclosing and avoiding situations in which there is a real or potential conflict”.

She also lists some specific laws and policies.

They are:

– Section 13(7) of the Australian Public Service Code of Conduct (the requirement to avoid conflicts of interest and to disclose details of personal interests)

– Section 14 of the ASIC Code of Conduct (the requirement to “disclose and avoid” situations in which there is a real or potential conflict between personal interests and duties to ASIC)

– Sections 15, 16 and 17 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (including the requirement to “promote the proper use and management of public resources”; to ensure officials “comply with the finance law”; to implement proper systems of “risk oversight and management”; and to ensure proper internal control mechanisms)

Source: “Abridged” Thom review, produced by Treasury.

Then Thom, as per the terms of reference handed to her by Frydenberg, puts the matter back in the hands of Treasury.

She states (at least according to Treasury’s 41-page abridged review) that: “The review recommends that, based on the evidence available to this review, it would be reasonably open to Treasury to obtain legal advice about whether Mr Shipton (sic) conduct, in the period from 11 August 2020 to 25 September 2020, may amount to a breach of section 14 of the ASIC Code of Conduct or any other obligation”.

“Achieving our Vision depends on the integrity of our people,” Shipton writes in ASIC’s Code of Conduct ….. which he now claims he is isn’t bound by. Source: ASIC

Code Red

Treasury’s 41-page document shows that, remarkably, Shipton (via his lawyers) responded to Thom that he had not been bound by ASIC’s own Code of Conduct.

That is despite Shipton himself having co-written it.

Thom states that Shipton “was offered an opportunity to comment on a draft version of this report” and that “his legal counsel advised” that:

‘While on its face the Code of Conduct states that it applies to ‘ASIC’s Commission members’, as a matter of law, the Code cannot and does not bind the Chair….(The) ASIC Act applies the ASIC Code of Conduct to staff employed by the Chair, but does not apply the Code to the Chair’.

In response, Thom states the following:

“Prior to 1 July 2019 the Chairperson was subject to the APS Code of Conduct as set out in s13 of the Public Service Act 1999. The following element of the APS Code of Conduct is relevant to this matter:

(7) An APS employee must:

(a) take reasonable steps to avoid any conflict of interest (real or apparent) in connection with the employee’s APS employment; and

(b) disclose details of any material personal interest of the employee in connection with the employee’s APS employment”

Thom also points to ASIC’s current Code of Conduct, written in July 2019.

And to the fact that Shipton himself co-wrote it.

Its first page is comprised of a “Message from the Chair” – “James Shipton”.

“The purpose of ASIC’s Code of Conduct is to guide our behaviours, choices and how we undertake our duties,” Shipton writes.

“The Code sets clear expectations about the standard of professionalism expected of everyone who works at ASIC and how we interact with each other and our external stakeholders.

Shipton, the head of Australia’s corporate corruption regulator, also adds:

“Achieving our Vision depends on the integrity of our people”.